Which country is winning the race to a circular economy? It’s not something one country can achieve by themselves, but in recent years, certain nations have taken the lead by clearly embarking on major circular economy agendas.

The motivations can vary, from creating a more competitive economy or meeting the needs of a growing population, to complying with emissions targets and better social outcomes. The move from an economy based on extraction and consumption to one of regeneration and restoration has become an increasing priority for policymakers around the world.

As Head of Public Affairs at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Joss Blériot has watched this unfold since 2012, when the Foundation was invited to sit on the EU Commission’s Resource Efficiency Platform. We spoke with Joss to understand the policy landscape across Europe and beyond, what’s motivating different nations to create circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. plans, and when the topic might eventually become an attractive proposition beyond business circles — a model for thriving societies, and something citizens could be compelled to vote for.

Maybe you can start by giving us an overview. In terms of the development of circular economy across Europe, are there any geographic trends? Any hotspots?

From a European perspective it’s clear that the EU Commission has taken the lead on this, seeing as the principle of a circular economy package was adopted in June 2014, which is quite a long time ago already. At the time, no member state had come up with a national roadmap, and it was very much the hope of the Commission that they would pick this up and start implementing it. What we see now is that to a certain extent, that call has been heard. Finland presented its roadmap last year, France has just published one, Slovenia published its own strategy in May, Italy has revealed the building blocks of its roadmap… Germany has been working on bits of a circular economy, although their definition is closer to resource efficiency, which is something that they have been involved in for a long time already. So there’s a convergence of signals that says, from a European perspective, the impetus was given by the Commission then it trickles down to member states. And of course, the Dutch were advanced before the circular economy package was announced, yet it wasn’t a fully-fledged national roadmap.

What I’m getting at with this is the fact that Europe started looking at this from two different perspectives. One was the fact that geologically, it’s a relatively poor continent. We don’t have a lot of resources. We don’t have a lot of room either, to bury the waste. At a moment when it was key to start thinking about a new growth and competitiveness agenda, which was the mandate of the Juncker commission, it became evident that something which had a potential attraction for business was also a very good idea. So there’s a combination of favourable elements in the landscape, and a desire from European institutions to kickstart a new wave of growth based on a different proposition: reconciling economic growth with environmental benefits, by moving to regeneration and restoration rather than extraction and consumption. Back in the early 2010s, resources prices and volatility soared, the financial crisis was in full swing: suddenly things were not cheap anymore, to put things simply, so generating revenue by feeding on easily available resources did not seem like a promising avenue.

You’ve mentioned examples from France, Germany and the Netherlands, some of which build on pre-existing themes. Is circular economy something new, or a continuation of ongoing efforts? Are conversations emerging from the environmental departments or elsewhere?

The way circular economy will be picked up in Germany depends on the government that was formed earlier this year. But the main differences you can see between Netherlands and Germany is that Germany, being a very heavy industrial economy, has looked at this through material flows and material availability. They need a lot of stuff to build their cars, their heavy machinery — it’s really important for them to have a critical raw materials strategy. They have had since 2010 something called the German Mineral Resources Agency, which deals with those flows. More recently, we’ve been involved with the “Deutschland entkopppelt” initiative, with Acatech and SYSTEMIQ, which promotes industry leadership around circular economy.

So it’s largely a top-down materials management strategy, which has some elements of circularity because you’re going to recapture some materials and make sure you don’t have any processes that jeopardise the availability of materials.

In the Netherlands it’s been more from an entrepreneurial angle, innovation in materials, business models, because that’s the type of economy they have. There’s a lot of service, they’re very nimble and agile, very open to new ideas. There was a circular economy initiative in 2008, which sat within the Ministry of the Economy and created a market, as there were some public procurement rules about circular products and services. And that really helped as well.

Regarding the French example, the circular economy roadmap in France is co-owned by the Ministry of the Ecological Transition and the Ministry of the Economy and Finance, which is really a first, as typically the French government is very siloed. To see this co-ownership of the topic says a lot about the transverse, horizontal nature of the change which is required. It does also highlight the need for collaboration — something which is often talked about.

I heard they’ve done something similar in Italy.

I think it’s well understood that this is a transversal topic and that it needs collaboration across all departments. Having said that, between acknowledging it and actually doing it there’s a big margin. And the Commission really pushed on this when they asked the Secretariat General, which is a coordination mechanism that deals with all the Directorate Generals, to be in charge of circular economy and to coordinate. So I think that message does permeate, and people that take circular economy seriously as system change can’t pretend that one department can do it by themselves.

What’s more, the smaller states have a tradition of collaborating simply because they’re smaller and more agile. Finland has been extremely collaborative with its roadmap and it was the first one actually published. Because it was the first one, other governments tend to look at it and say ‘how have they done it?’ and replicate the bits that work and that they can adapt.

That could paint a bit of a rosy picture. Having said that, if you want to look at an impartial assessment, the European Environmental Agency, which is an official body of the European Union, has examined circular economy and resource efficiency policies across 34 countries. It published the findings in a report called ‘More from Less’ that shows that even if it is going in the right direction it’s still very waste oriented. It’s focused on waste management. It’s still hard to get into the upstream issues.

So what are some of the themes we’re seeing emerge?

There is clear indication that Europe wants to create a strong market for organic fertilisers and gradually phase out petrochemical ones. It’s interesting that this was one of the first bits to come out of the circular economy package, because it acknowledges the bio side of the economy which is quite rare.

The organic fertiliser theme has emerged because of the circular economy momentum, and the fact that agricultural policy is being reformed. So it sits at the crossroads of two really big strategic things for the Commission, and it’s vital that this bio side of the economy is taken more and more into account.

There’s more we can learn from the example in Finland. They have a circular economy strategy and bio-economy strategy, and to a certain extent people didn’t seem to understand that they were the same thing, or that one was part of the other. They have been pitched up against each other sometimes, which wasn’t helpful. All of this means that we’re starting to see a picture emerge whereby legislators gradually understand that you can’t just take one topic and implement circular economy through one lens only.

Of course, much of the momentum has originated from the waste management, anti-pollution and environmental agenda. Generally, policymakers tend to look at the materials and waste reduction and sometimes the design aspect. In fact, I understand that the Spanish initiative is quite focused on design.

But people recognise more and more that it really is a question of shifting the system towards something which is more competitive and has many benefits. It’s gradually becoming a topic that absolutely everyone can get a hold of. It’s not somebody’s turf.

With momentum growing so quickly, can you see any untapped or missed opportunities?

It’s definitely the upstream aspects, which are creeping up the agenda but are still under-represented. Circular economy activity so far has mostly been associated with waste management, and emerged out of downstream considerations. That’s where the first pockets of interest have been found, and because of the pressing issues of tighter regulation, more visible pollution, and more scientific proof of its impact. There was also a period in the early 2010s where volatility and price hikes meant that a business couldn’t afford to go through virgin materialsvirgin materialsMaterials that have not yet been used in the economy. at a stupid rate, simply because it wasn’t economical. All these things combined meant that circular economy started to get traction in that area, downstream.But clearly, if you are going to capture and cycle materials, you have to design products differently. You have to use materials that don’t contain toxic substances. You don’t want to contaminate your systems if you’re going to start making them cyclical — this is why looking at chemicals in the context of circular economy is an emerging topic, one that will prove crucial in the near future.

So some of those earlier motivations behind the circular economy have changed, but they’ve left a legacy of how the topic is perceived now?

Exactly. And you have to remember that when the Juncker commission came into office and hinted that they might push circular economy aside because it was perceived as an environmental agenda, there was backlash from some of the early big private sector adopters. Suez, Philips, Unilever and Michelin sent an open letter to Juncker saying ‘don’t drop this’. That was a proof point that there is something to the circular economy that’s bigger than the waste agenda. And once these businesses decided that it was a good idea and that they would invest in looking at either new materials or business models, of course they would start looking upstream. So it’s not an untapped opportunity as such, but it should be very clear that the urgency is to look at the upstream aspects.

One of the really important things to stress is that the linear economylinear economyAn economy in which finite resources are extracted to make products that are used - generally not to their full potential - and then thrown away ('take-make-waste'). created this sort of race to the bottom, in the sense that the businesses want to maximise their profits and regulators were there to curb the excesses. Going into the policy discussions with that sort of tension and different agendas meant that you all too often ended up with the lowest common denominator. The circular economy is a direction that both the public sector and companies can agree is a good one. And let’s not be completely naive, of course there are vested interests and tensions along the way. But if we identify that this is going to be an opportunity for everyone and that everyone will benefit from it because the system is much better, then we can focus on creating the right level of innovation with the right guarantees for the public as well, in terms of safety and so on, and that it’s done in a fair way.

And the European Commission deserves some credit for the ‘Innovation Deals’ mechanism they’ve created — taking lessons from the Dutch Green Deals, which is something France has emulated as well since 2016. Say you’re a business, you want to invest in circular economy, but something prevents you from doing it. You go and make the case to the Commission, they analyse the regulation and if appropriate lift that barrier as an experimental measure. It really shows that there’s a willingness from the regulators to understand what stands in the way. So that co-creation process to a certain extent does exist.

Much of what we’ve discussed so far relates to government departments and legislation. Is circular economy political? Is it something people would actually vote for?

It would be great if it was something to vote for. Every economic model shapes the society it operates in and if this one is as positive as we tend to describe it, then it should be something that people can vote for. The challenge is the narrative and making sure that people who are putting that to the public describe it in a systemic way. As long as it’s seen as a waste-oriented agenda, it’s going to be associated with lower quality products, less choice, sacrifices. And that’s going to be extremely boring. This is why getting the language and the proposition right is so important. Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle co-creator, was right when he said that simply looking at “less bad” and “sustainable” as core values was misled: a positive vision, describing a beneficial model, is required here.

Looking outside the EU, how about China and Japan? How do their circular economy practices differ from Europe?

China has had circular economy in its policy since the early 2000s. It was part of the eleventh five-year plan and we’re currently on the 13th. To begin it was primarily an industrial ecology agenda, looking at how the waste of one company can become resources for another. It was very much end of pipe, the three R’s. Reduce, reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification., recyclerecycleTransform a product or component into its basic materials or substances and reprocessing them into new materials.. But the latest Circular Economy Policy Portfolio, which came out in 2017, looks at eco-design (both as a concept and as a policy) and extended producer responsibility and it��’s a massively important step. It shows the importance of upstream. A lot of cities are also looking at circular economy so it seems that the Chinese perception of the concept has evolved massively. And coming from a pure ‘how do we manage the flows’ perspective, it’s become an innovation agenda.

What’s more, the Chinese economy has matured. It’s not just the factory of the world, churning out cheap products. It’s also an economy that is growing in investment capability, in innovation, embracing digital massively, and which has serious environmental problems that they have to deal with. All these angles converge towards a reshape of the overall system. And then because they have the building blocks of a circular economy in their legislation already, then they are making those gradual steps towards something which is more all-encompassing. It’s very interesting.

Japan is somewhat different: in the late 90s and early 00s, they had a very comprehensive exercise of mapping all the material flows, so what’s coming in and what’s going out, asking ‘how can we make better use of it?’, because Japan is very resource and space constrained. They’re also a very advanced economy, with a lot of precise industrial processes in place. Some exercises, such as the Lean Manufacturing strategy that was implemented by Toyota, have made a big mark on people. But to be clear — I’m not saying there’s a direct link between Lean and circular, the point here is that Lean involved a major mindset shift, it questioned the existing processes and therefore opened the door to different approaches. It’s been seen as very influential, and a natural evolution from this is to ask how to improve remanufacturing, how to keep those materials in the system. It is still evolving, and coming from the same sort of pure material flow, pure industrial policy, into something which is more aimed at design.

The G7 has a group called the Resource Efficiency Alliance. It’s been very receptive to circular economy ideas. On the topic of the G7, the International Resource Panel has been mandated officially by the G7 to come up with guidelines and advice for policymakers which is very good. The G7 also raises the question of the US…

Go on…

The previous administration was quite interested in the idea, mostly from the angle of vehicle remanufacturing. And all I can hear now is very loud silence coming from the Americans at federal level. But we know that in pockets, cities like New York, Phoenix and states like California, Colorado and Washington there is interest. Rochester Institute of Technology and the Sustainable Manufacturing Innovation Alliance received money from the Department of Energy to lead the REMADE Institute. It was signed during the previous administration, but in March funding was approved through to 2019.

Why doesn’t the jobs, growth and competitiveness theme that is driving circular economy momentum in Europe work in the US?

The unemployment rate is very low, growth is good… They have plenty of energy, they’re going to be a net exporter. They have plenty of room to landfill the unpleasant by-products of the linear economy if they want. Compared to Europe or countries like Japan, the context is considerably different, both in terms of sheer availability of resources and of space, as well as when it comes to political priorities at federal level.

But policy issues can cross continents, such as China’s decision to ban imports of plastic. Could that become a factor?

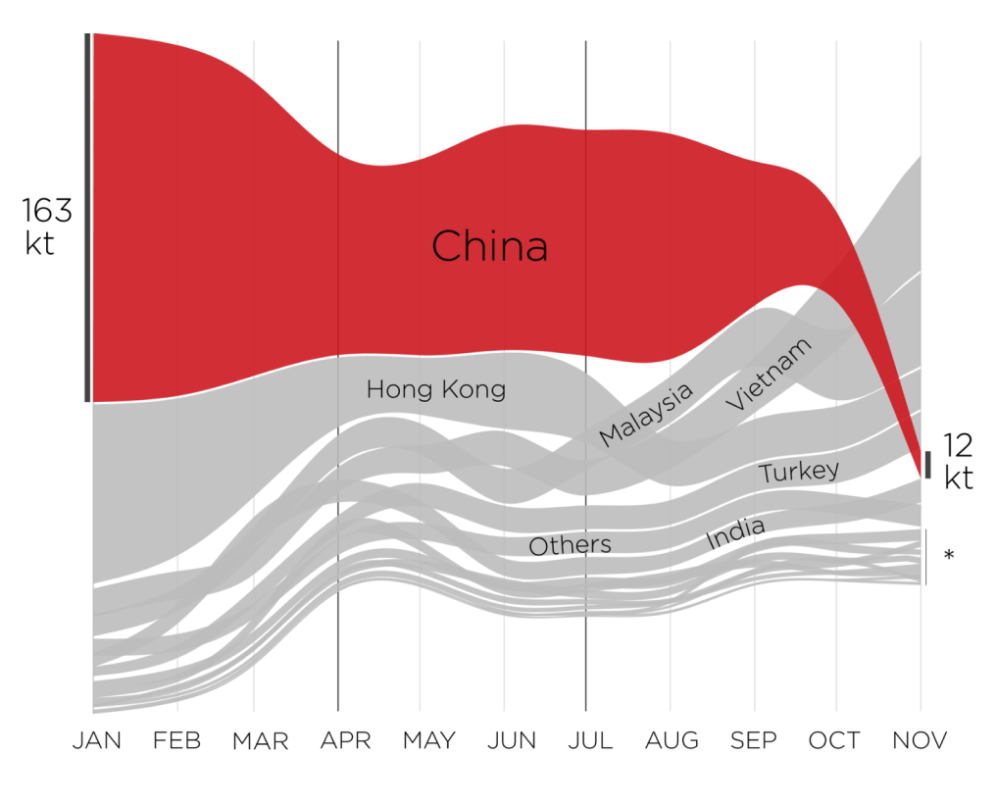

It’s of course difficult to say just how much it is a factor, but it certainly is one. The national Sword policy is basically a message to Western economies, loosely interpretable as ‘don’t send us your rubbish anymore’. The speed at which it’s had effect in Europe is absolutely incredible. If you look at the flow charts of materials, it shows how quickly it became a problem for the exporting nations.

And that of course is going to have an impact on policy. The fact is that exporting countries will now need to deal with their stuff, and because there are countries that don’t really have a lot of wiggle room for that, then it’s going to become a very big issue very quickly. The logical step would be to make design changes and to be a bit more drastic about what you can and cannot use. To look at it simply, in some cases the stuff that some countries used to send abroad is going to end up on their soil, and what if it’s contaminated? Then it could infringe their own regulation… and what government likes to be seen as incoherent in their policies.