In this deep dive, we explore how and why systems and systems thinking are so integral to the circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. concept.

The blind men and the elephant

An old story with a timeless message

An ancient Sufi story tells of a city whose inhabitants were blind. One day a king arrived riding at the head of his army on the back of a mighty elephant. Curious to know what sort of animal it was, some of the blind men rushed forward to touch the elephant. One man, feeling the elephant’s trunk, claimed it was like a giant snake, strong and powerful. Another man, touching its feet, said it was like a sturdy tree trunk. And so the quarrel continued with each man claiming that his impression of the elephant captured its true form and likeness.

The lesson is simple: to understand something properly, the parts must be understood in relation to the whole. This story has universal appeal because its essential truth can be applied to all phenomena, from animals to economics. As John Muir observed, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." The key, therefore, to real understanding is understanding relationships.

What does this have to do with the economy?

Firstly, it is important to understand some of the relationships that shape our economy.

At its most basic level an economy is the name we give to a process: society making use of natural resources to create products and services that people need or want e.g. homes for shelter, and food for nourishment.

Viewed in this way, our economy, society, and environment are interdependent systems - the vitality of one affects the vitality of them all. This is the simple yet profound reality that begins our understanding of systems.

Our linear economy

Yet as obvious as this seems, we have an economic model based on extraction and depletion, which disturbs the vital equilibrium that exists between the economy, society, and environment.

Our linear economy is consuming the earth’s finite natural resources, leading to high levels of waste and pollution that threaten the biosphere and human health. If we fail to see the economic, social, and environmental spheres as intimately connected we will miss the point; just as the blind men misunderstood the elephant. And we will continue to undermine our chances of future prosperity.

The world as machine

If we are to transition to a circular economy, we need to start thinking differently.

The dominant scientific mode, particularly in the west, has been to understand things by analysing individual parts in isolation. This method, known as reductionism, has become the filter through which we see the world, influencing our thoughts, language, and actions. One of its lasting and most misleading legacies is the notion of the world as a machine i.e. predictable, understandable, and controllable. Our current linear economy is one example of a man-made system that reflects this. It is like a machine - resources go in and waste comes out, a conveyor belt process in which the primary goal is to increase efficiency and drive endless economic growth. It is an abstracted economy, divorced from any connection to the broader natural and social systems that maintain it.

What is a system?

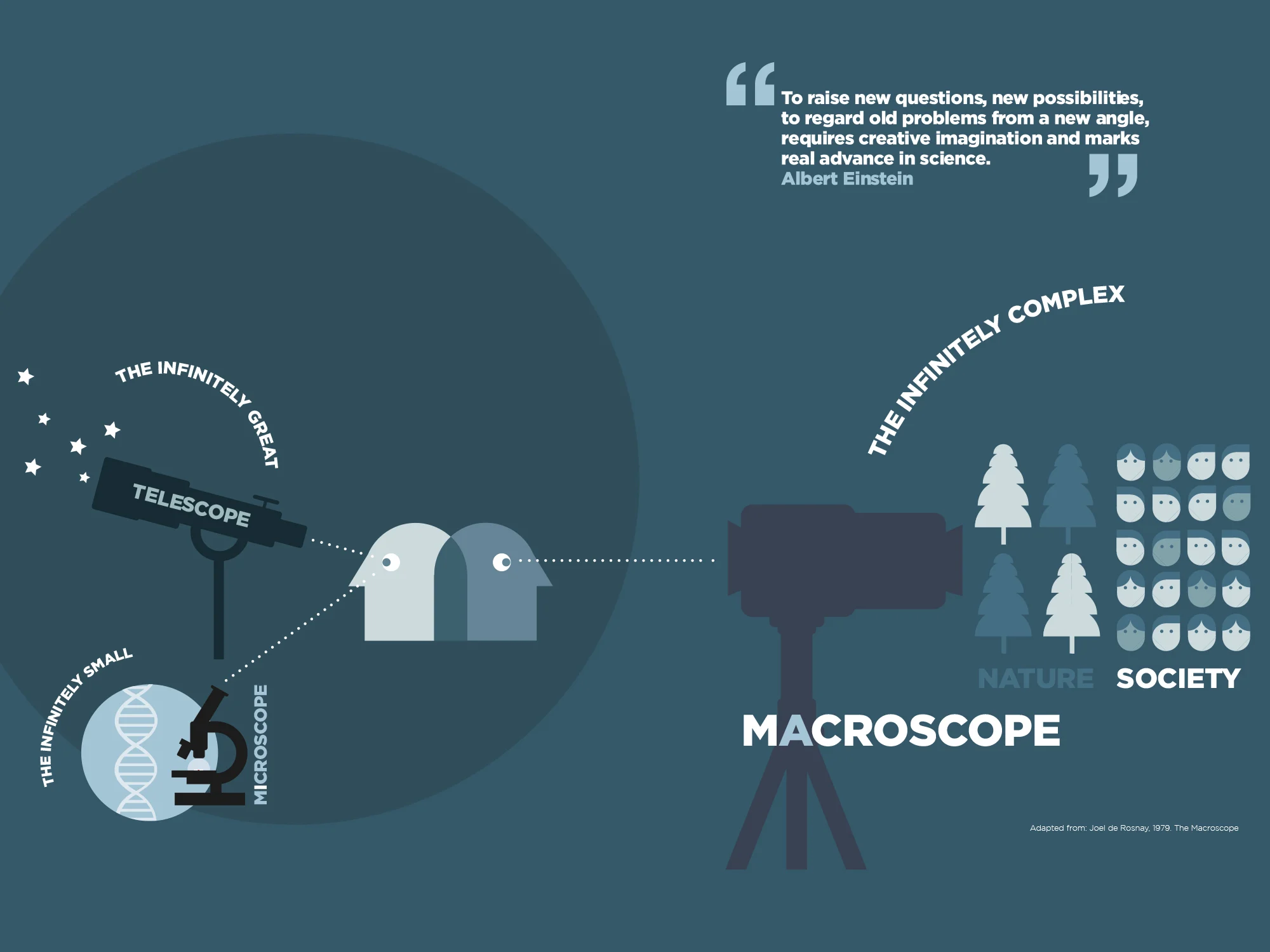

So what tools can we use to help us make sense of the whole not just the parts? One tool is systems thinking. But before we explore systems thinking we first need to understand what a system is.

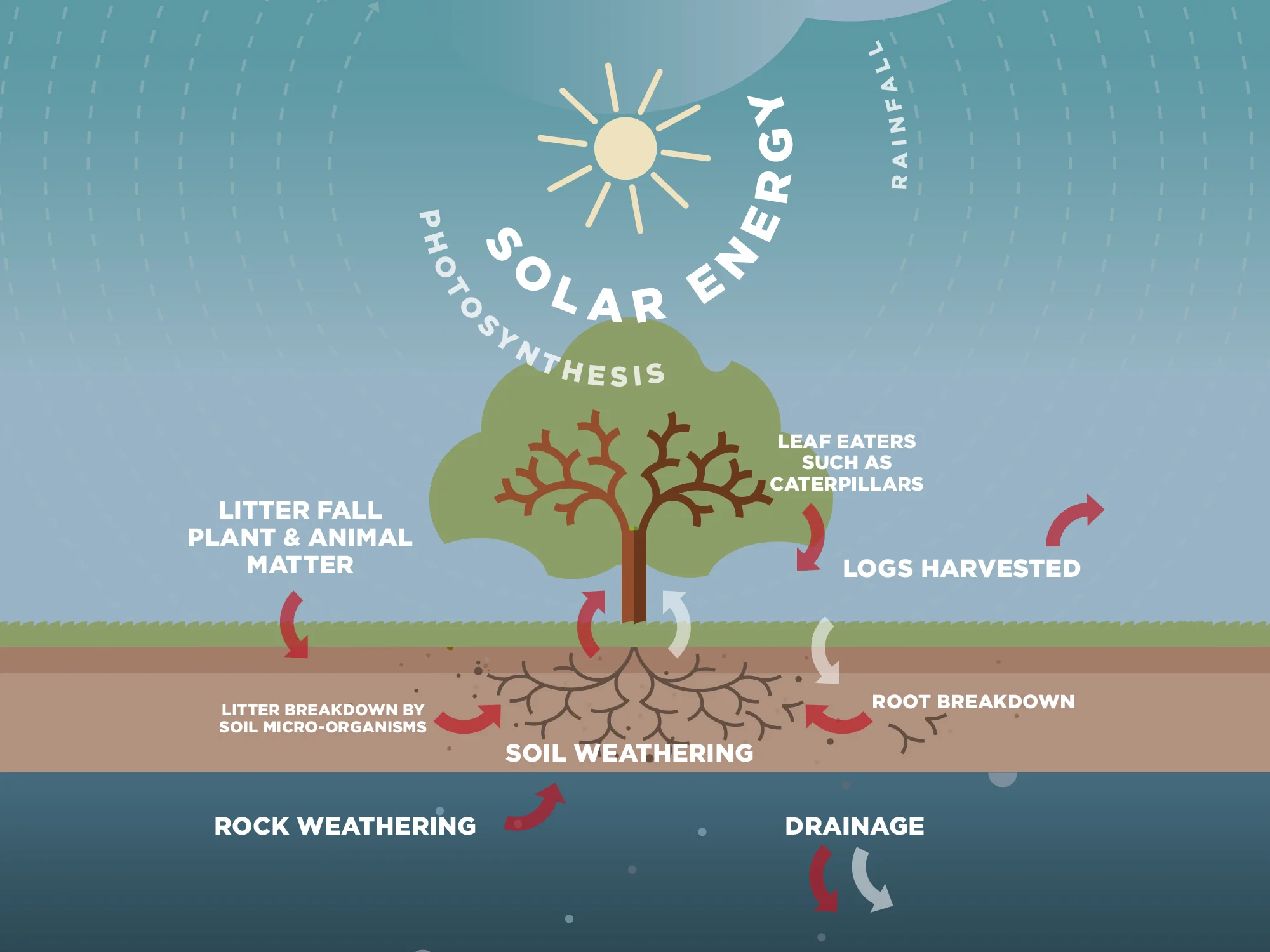

Systems expert, Donella Meadows, describes a system as ‘an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organised in a way that achieves something’. In a forest there are many elements that determine the overall health of the system, including the soil, plant life, animals, insects, and bacteria. Take insects, for example, they aerate the soil, pollinate blossoms, help control pests, and decompose detritus and foliage that helps build a nutrient-rich layer of soil that supports plant growth. Remove insects from the system and it will have far-reaching consequences.

Systems thinking

What is it?

Systems thinking is the ability to understand how the parts of a system interact to produce the behaviour of the whole. Donella Meadows describes it as a ‘way of thinking that gives us the freedom to identify root causes of problems and see new opportunities’. At the opposite end of the spectrum, if we apply reductionist (i.e. linear cause and effect) thinking to complex problems we will likely arrive at solutions that lead to unintended consequences.

Taking on the challenge of complexity

Some of our most pressing challenges - such as how to tackle climate change or ocean plastic pollution - are extremely complex challenges.

If these were merely environmental challenges, solutions would be easier to implement; but they are also social and economic challenges. Ocean plastic, for example, is a result of our reliance on single-use plastics, lack of consumer education and awareness, poor product design, business practices and incentives, and a lack of finance and infrastructure among other things. We cannot form a true understanding of these ‘systemic’ challenges unless we can appreciate how all of these elements interact to produce certain dynamics and behaviours. If we don’t understand the problem we cannot arrive at an adequate solution. So how might we apply systems thinking to our entire economy?

The role of systems thinking

Systems thinking plays a dual role in the circular economy. It is an enabling tool that can help us identify root causes and implement better solutions, and it provides the lens or frame for our conceptual understanding of it.

Even the most cursory study of living systems reveals a few key principles: waste goes to productive use, cooperation and interconnection across multiple scales are crucial, regeneration occurs naturally over time. In seeking to apply these insights, the circular economy comprises three core principles: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials, and regenerate nature.

As leading circular economy thinker, Ken Webster, points out, the circular economy is ‘a story about the possibilities of abundance, of meeting people’s needs by designing out waste, and recreating the kind of elegant abundance so evident in living systems.’

Pause for thought

In many ways the story of human evolution and progress has taken us away from our intuitive understanding of systems and how to work with them. What benefits might there be in reclaiming this understanding?

The wisdom of the cherry tree

The living systems analogy is a strong theme in the work of Michael Braungart, co-founder of the Cradle to Cradle design concept, which is a central pillar of circular economy thinking.

In The Wisdom of the Cherry Tree, he explains that effectiveness rather than mere efficiency should be the end goal for an economy:

‘The cherry tree is just one part of a much bigger, interdependent natural eco-system and it is this interdependence that matters. For example, the blossoms of the cherry tree not only bring forth a new generation of cherry trees… they also provide food for micro-organisms which in turn nourish the soil and support the growth of future plant life. The ‘outputs’ – indeed ‘waste’ – of one process (the cherry tree and its blossoms) have become inputs for other processes. When viewed in isolation, each element within this natural system may be highly inefficient. But as a whole, the system is stunningly effective – and doesn’t produce any waste at all. We need to apply the cherry tree’s wisdom to the world of production and consumption.’

Context and connections

In his book, A Wealth of Flows, Ken Webster draws on the systems perspective and its implications for the world of business:

‘A systems understanding reminds us that survival of the fittest means the firm which fits best into its context - and context is inescapable. The strongest trees are in the healthiest forest.’ To understand the importance of context and connections, let’s look to the story of the ancient civilisation that built the stone heads of Easter Island. This timely lesson from history teaches us that failing to understand our interconnectedness with the systems we depend upon can have catastrophic consequences.

A flow of wealth or a wealth of flows

Circular economy writer and thinker, Ken Webster, debunks some of the commonly held myths surrounding the economy and paints a vision for an entirely new model based on our understanding of living systems.

Conclusion

The systems perspective allows for a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the economy as one part of a much larger whole.

It also disabuses us of the belief that we have control over the economy. The living systems analogy provides us with a new metaphor - the economy not as machine but as a forest. Rather than mere throughput of materials, it is the circulation of materials that allows life to flourish - things grow, they die, and then nutrients are returned to the system to feed new life. The success of the forest is not measured by the endless growth of its trees but by its ability to reach maturity and thrive in a state of equilibrium with all that surrounds it.

Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, talks about how we might reimagine the economy:

-----------------------

Funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation