Introduction

Mapping a system is to bring to the surface the different elements that constitute that system, as well as their interconnections and interdependencies. When visualising systems that relate to the circular economy, common elements include actors, activities and events, resources and information, policies and incentive structures, and the flows and relationships between them – all of which need to be viewed in the context of the whole. This process reveals the nuanced forces that influence the system in question, and surface why it might produce certain positive or negative outcomes today.

It’s been said that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets” – so it’s always good to ask how did the system you’re investigating end up working the way it does today? When designers spend time observing and interpreting the system, they develop an understanding of how it has evolved over time, in addition to appreciating its strengths, constraints, and uniquenesses. For example, for an organisation using a biobased material, creating a ‘birds eye view’ of the product life cycle might enable them to see that a lack of proper infrastructure prevents their products achieving full biodegradation.

In addition, harnessing the features and forces already present within a system can be an effective way to create greater impact from a smaller shift. For example, when designers mapped and integrated three interconnected layers – the farm landscape, the cultural landscape and ecological restoration – they were able to transform Orongo Cattle Station,a 3,000 acre coastal farm in New Zealand into one of the richest and most biodiverse ecosystems in the region.

As such, locating an organisation, material, or asset within a wider context can reveal the most impactful opportunities or intervention points to begin shifting from linear to circular.

Mapping material flows within a city, a value chain, or an industry will expose where materials are lost from the economy. This gives an entry point from which to discern upstream opportunities to eliminate waste, circulate products and materials, and regenerate nature.

“The design brief has been going in the wrong direction – trying to isolate the problem, rather than show the full complexity of it. Therefore we lock a solution onto an isolated problem.”

- Bruce Mau, Designer, Author and founder of Bruce Mau Design Studio

The process also helps identify relevant collaborators or focal points for collaboration. For example, a range of fashion brands may not work together on the final design of garments, but they could collaborate to scale regenerative sourcing, reusable packaging solutions, or digital infrastructure to enable rental models. Similarly, connecting with collaborators elsewhere in the system will likely show that other stakeholders have partial solutions or a different piece of the puzzle. Surfacing and exploring these connections helps organisations to avoid reinventing the wheel or ‘going it alone’.

“You can’t design the strategy until you understand the complexity of the system.”

- Chris Grantham, IDEO Alum (former Executive Director, Circular EconomyCircular EconomyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature.)

Perhaps most importantly, when organisations understand the systems of which they are a part – both the internal dynamics and those of their industry or region – they are better placed to act systemically and strategically. A systems overview avoids isolated efforts where they may be ineffective; it also helps identify potential rebound effects or unintended consequences. For example, carbon offsetting looks at compensating carbon emissions, however, if not considered holistically, this action can jeopardise other aspects such as biodiversity or air quality.

“It’s about holding the fullest complexity. Usually within design we like to narrow our brief down, to refine and refine it. Holding the fullest complexity means understanding that complexity still exists.”

- Cat Drew, Chief Design Officer, Design Council

Anyone can get started with mapping systems – simply by taking a material, product, or service and asking what happens next and why? However, the skills of designers enable organisations to generate richer observations and more thoughtful interpretations of system dynamics. Activities that design teams will be familiar with – such as design research, journey or user experience mapping, and service blueprinting – will help organisations accelerate the transition to a circular economy.

How to approach it

Decide what’s in the system

Drawing boundaries around a system from the outset can help to manage its complexity, and create entry points from which to begin mapping. The system scope can be as large or small as the enquiry or design brief dictates. For example, it could centre a value chain or a single organisation, a region or a neighbourhood.

“There are no separate systems. The world is a continuum. There is no single, legitimate boundary to draw around a system. We have to invent boundaries for clarity and sanity; and boundaries can produce problems when we forget that we’ve artificially created them. Where to draw a boundary around a system depends on the purpose of the discussion—the questions we want to ask.”

- Donella Meadows, environmental scientist and systems thinker

Meadows, D. Thinking in Systems: A primer (2008)

Map the system

Surface the material flows and exchanges within the system. Where does material leakage occur and where do harmful practices degenerate natural ecosystems? Identify clusters of key actors within the system – their circular economy readiness and the interactions between these key actors. Where do their missions overlap? Which forces are driving a circular paradigm shift and which ones are holding linear systems in place? Note where within the system circular economy activity is already underway. How can we build on current efforts and where are there innovation gaps?

Ensure inclusive representation

Include diverse perspectives – whether local business, citizens, or users – within the systems mapping process to create visibility of needs, interests, challenges, and hopes at the outset. This will surface impactful circular economy opportunities, enable the participatory design of interventions, and avoid overlooking underrepresented groups later in the decision-making phase.

“Looking at a system from different perspectives means to understand the agency of each organisation within the system; their views of the system and their relationship with the system. Asking questions such as: What is value to them? What are they trying to achieve? And what does that mean in terms of how they will re-orientate? Will help create a common understanding.”

- Joanna Choukeir, Director of Design and Innovation, The RSA

Examples

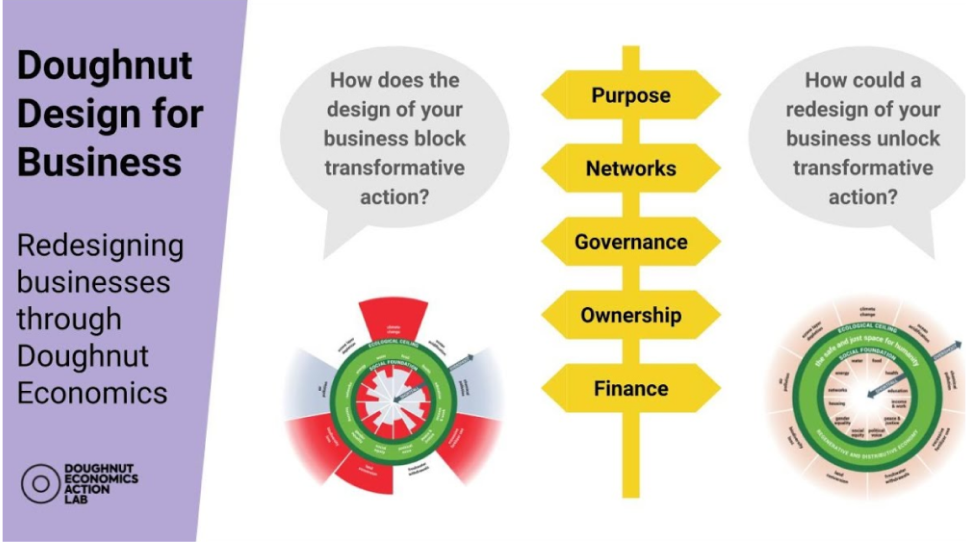

Doughnut Design for Business

By: Doughnut Economics Action Lab

Scope: Organisation

Purpose: A tool for business to explore five layers of deep design, revealing organisational blockers for transformative action to redesign the business and unlock its possibility.

Approach: The action-oriented workshop enables businesses to assess the current business design through the lens of five deep design layers: purpose, networks, governance, ownership, and finance. The workshop helps to generate transformative ideas to redesign the business for a regenerative and distributive economy.

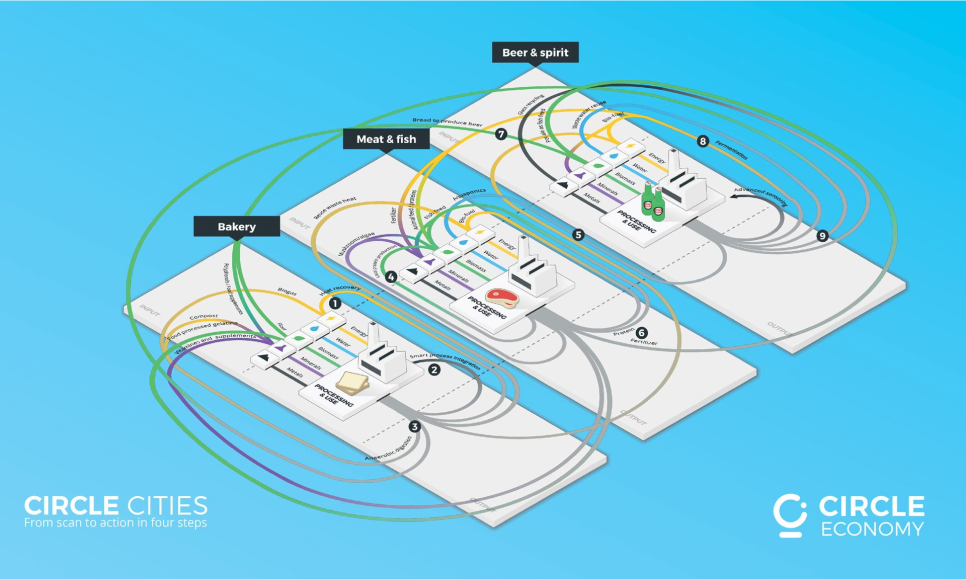

Glasgow Circle City Scan

By: Glasgow Chamber of Commerce and Circle Economy in partnership with Glasgow City Council and Zero Waste Scotland.

Scope: City

Purpose: A systems mapping exercise to identify opportunity areas to make a city more circular, support local businesses,, and identify where to start.

Approach: The spatial maps explore the economic and environmental impacts of material flows in key sectors (healthcare, education, manufacturing), as well as geographically surfacing clusters of key actors within Glasgow.

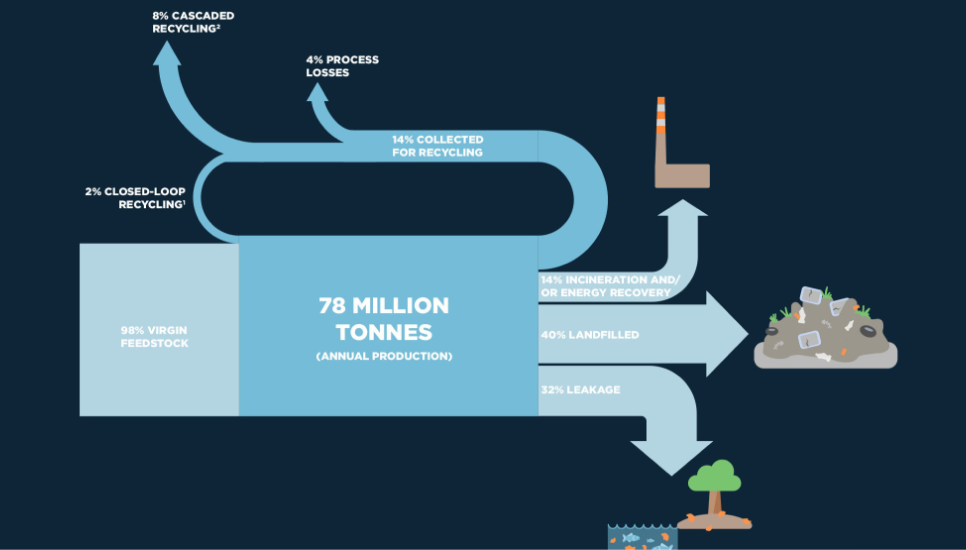

The New Plastics Economy: rethinking the future of plastics and catalysing action

By: Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Scope: Plastics Industry

Purpose: A systems mapping exercise to understand the current production, use, and leakage of plastics within our economy.

Approach: The report analyses material flows to describe the high level of urgency regarding the plastics industry. It does so by mapping historical and potential growth in plastics production, different types of plastics and their use, value leakage across systems, significant negative externalities associated with its production, forecasted use and current innovation efforts. This presents a clearer idea of opportunities, leading to the creation of a vision for the New Plastics Economy.

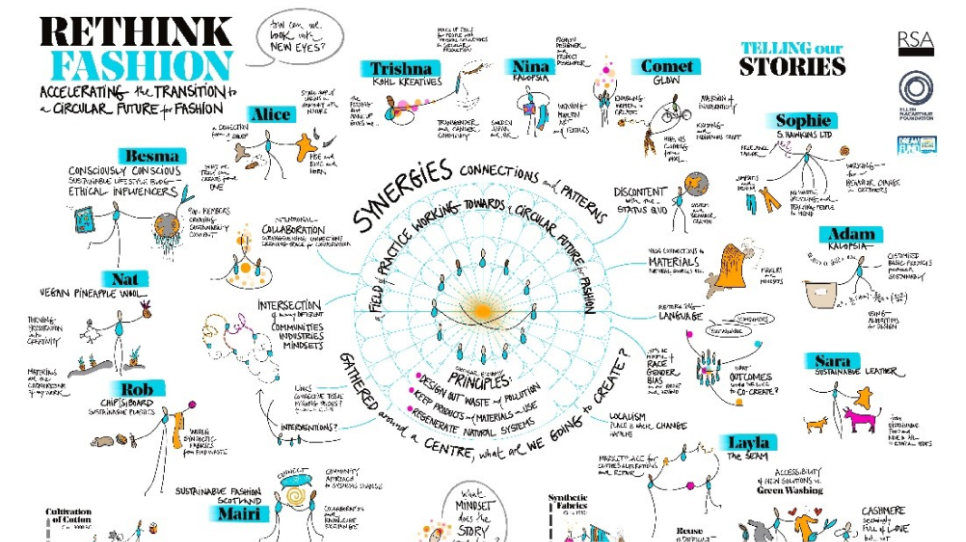

Rethink Fashion

By: The RSA

Scope: Fashion Industry

Purpose: A systems mapping exercise to envision the future of fashion at different levels of the system.

Approach: The map uses the multi-level perspective – a prominent transition framework (Geels) – to explore how the pioneering ideas, practices, and innovations in fashion at the micro level intentionally work together to influence institutions, funding systems, and incumbent organisations, as well as the macro environment of laws, regulations, and societal norms.

Next: Envision circular futures

Imagining circular and regenerative futures at different scopes such as the food products we eat, how circular businesses might operate, or a circular city might function.