At a glance:

Each year hundreds of millions of tonnes of organic material flows out of our cities

98% of this material ends up in landfill, incinerators, or rotting in open dumps, representing a loss of value, a source of pollution, and a risk to public health

Meanwhile, we continue to extract virgin material to make new consumer products

What if organic waste from our cities could provide the feedstock for high value products and help build a circular bioeconomy

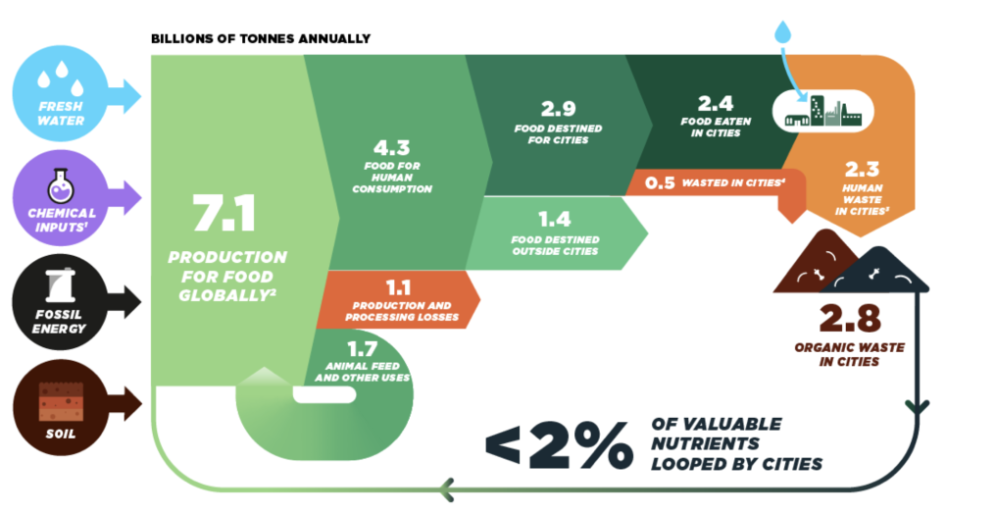

Less than 2% of organic waste is valorised

There is great unrealised potential in the high volumes of discarded food waste and by-products that flow out of the world’s cities. In the current take, make, waste, linear system less than 2% of these valuable nutrients are put to productive use. The remaining materials typically end up in rivers, landfill, incinerators or in open dumps, where they can be a health hazard, a source of carbon emissions, and lead to many other potential costly impacts.

The first step to reversing this situation is more effective collection systems. Working examples in place today shed light on ways to improve collection and increase volumes. But having gathered the material, what’s next? How can the collected material be used to create new value?

The majority of current ‘bio-valorisation’ activities generate low to medium value products such as biogas, compost, and digestates. However, there is a growing interest in the production of high-value products, using processes that replace finite resource inputs with organic waste streams. A number of Italian companies are at the forefront of this new area of innovation.

From report: Cities and Circular Economy for Food

Fabrics from Oranges

The Mediterranean island of Sicily has the perfect conditions for cultivating oranges and other citrus fruit, which local companies then convert into food and beverage products. The processing of the fruit creates many thousands of tonnes of peel, a small proportion is used for cattle feed, but most ends up in landfill. In 2011, two Sicilian design students, Adriana Santonocito and Enrica Erena, asked themselves whether something valuable could be created out of this abundant resource. Observing that a large percentage of peel comprises cellulose, a material that had already been used to make fabrics such as rayon and viscose, they set about experimenting in how to turn citrus waste into a textile yarn.

After three years of hard work, the two friends had succeeded in creating a brand new fabric material and were ready to start approaching fashion designers and brands. The first customer was Italian luxury retailer Salvatore Ferragamo which incorporated the Orange Fiber twill (50% cellulose fibre from oranges and 50% organic silk) into their 2016 spring-summer collection. The successful collaboration led them to success at H&M Foundation’s Global Change Awards in 2016.

In Italy, 700,000 tonnes of citrus by-product are generated each year. Through imagination and an understanding of chemistry and material science, entrepreneurial companies like Orange Fiber are realising that these discarded resources are in fact feedstock for high quality materials of the future.

Image from Orange Fiber

Leather from Grapes

Italy is home to some of the world’s most renowned vineyards, including Barolo, Brunello, Amarone, and Barbaresco, along with thousands of other wine producers. Annually, the country bottles around 5 billion litres of wine, more than any other region of the world.

All of this wine requires a lot of grapes, resulting in a by-product called ‘marc’ (or ‘pomade’), comprising the skins, pips, and stems. In terms of volume, for every four litres of wine produced, one kilo of marc is generated. Grape marc can be used as a soil enhancer, but with care. Before use, pre-treatment is required to stabilise the material to avoid the release of excess tannins and phenols into the soil, which can inhibit plant growth.

A Milan-based architect called Gianpiero Tessitore realised that wine by-products also contain fibrous materials that can be used to make leather-type fabrics. Tessitore, in collaboration with a number of research centres and the University of Florence, has patented a wine leather production method, setting up a company called Vegea to commercialise his ‘grape leather’. The new material has got many big brands interested, not just fashion but also companies like Chevrolet, Honda, and Volkswagen, that now produce cars with vegan interiors.

Leather is just one of many products that can be derived from marc. The cosmetics industry has known for a long time about the exfoliating and anti-wrinkle potential of the polyphenols released in wine processing. The pharmaceutical industry is also interested in the compound resveratrol, with potential anti-ageing and anti-inflammatory properties, adding credence to the Italian proverb: “buon vino fa buon sangue*”

(*good wine makes good blood.)

Grape leather from Vegea

Paper from pasta by-products

If there is one food that is the symbol of Italian cuisine, it is pasta. From long threads of spaghetti to flat sheets of lasagne, most pasta types are produced from the flour of durum wheat, a very hard grain made of a tough outer bran and a starchy inner endosperm (also referred to as semolina). Unless the pasta is wholegrain, the production will only use the semolina. This means that pasta companies such as Barilla end up with lots of bran residue.

Enter Favini, a company that had already been successful in producing a line of paper called Crush using citrus fruit peels, lavender stems, coffee grains, and other food by-products. Barilla approached Favini to explore making a paper from the bran residue that they could not use in pasta production. The result is a fine paper called CartaCrusca, which contains 20% bran residue, replacing cellulose and filler materials from virgin sources.

Products like CartaCrusca and Crush demonstrate a double win: not only do they reduce the demand for virgin resources, they also create a new revenue stream from a material that would traditionally be discarded.

Image by Ombadesign from Pixabay

Transforming surplus milk

“In the future, you’ll be able to choose between drinking a glass of milk and wearing one.”

Pathé Films, 1937

According to waste research charity WRAP, each year in the UK we pour 290,000 tonnes of milk down our drains, making it the third largest discarded food type. This is perhaps not surprising. Milk is a fairly low cost and regularly used food product, so naturally we tend to overbuy. There are a number of ways of using surplus or even slightly spoiled milk in cooking, including making ricotta cheese, but however well we try to avoid wasting milk, there will always be a surplus to manage. Fortunately, there are uses for excess milk outside of the kitchen.

In the 1930s, an Italian chemist called Antonio Feretti pioneered the production of a new textile fibre called Lanatil out of excess milk. His success was based on a simple logical premise: if wool is a protein, and milk contains a protein (called casein), then can you make a wool like fibre out of milk?

Shortly afterwards, a new company was set up, called SNIA Viscosa. The aim was to commercialise the process, and the business received significant startup funds from the Italian government, who saw it as a way of achieving economic self-sufficiency. By 1937, 10 million pounds of Lanital were being produced per year. The company even broke into the lucrative US market, where the material was marketed as Aralac, used in high end garments, and later on in military clothing. Despite the early promise Lanatil fell out of favour, being much weaker than wool and liable to give off putrid smells when damp.

Many years later, an Italian company has resurrected the interest in fibres derived from excess milk. Due di Latte, a company from Tuscany, has refined Feretti’s process creating a collection of different fabrics derived from either 100% milk fabric or blended with organic cotton or plant-derived fibres. Blending imparts specific properties such as strength, softness, weight, luminosity, and breathability. Milk fibres also have hypoallergenic and antibacterial properties, so that besides comfort, the clothing nourishes and moisturises the skin.

These same qualities are being applied in the products of another Tuscan company called Tenderly, who have manufactured their new line of ‘Carezza di Latte’ toilet roll from 100% natural milk fibres.