Pioneering behaviour change towards procurement for circular economy in Malmö

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed life in cities around the world and has disrupted the systems that support them. But as restrictions in cities are eased and supply chains start up again, there is an opportunity to develop new systems that work better for people and the environment. The city of Malmö in Sweden aims to catalyse the transition to a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. in the Baltic Sea Region using public procurement. Part of the EU-funded Circular PP project, Malmö is piloting an approach to create a circular economy for furniture, focusing on repair, reuse and refurbishment.

Cities currently consume 60–80% of natural resources globally. However, with the aim to reduce their use of resources and overall impact on the environment, cities are increasingly signalling their commitment to transition towards a circular economy. To achieve this, many cities are focusing on implementation of resource loops as well as the creation of regenerative and adaptive urban areas. One powerful approach to steer the transition is to foster circular public procurement. This requires public authorities to think differently about the goods and services they need, and how to buy these in a way that considers the journey of products throughout their supply chain and use. By rethinking conventional procurement processes and business models, resource loops can be established within and across sectors.

The city of Malmö began to explore the potential of circular procurement in 2018, deciding to begin by piloting a procurement approach that could establish a circular economy for furniture. Centred on reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification. and refurbishment, and also emphasising existing services for second-hand items and repairrepairOperation by which a faulty or broken product or component is returned back to a usable state to fulfil its intended use., Malmö created a framework contract. The framework focuses on office and conference furniture; however, it can also be used by Malmö’s seven publicly owned companies. The creation of the circular framework agreement is already an achievement in itself, however the next frontier is to encourage buyers to use it as a preferred alternative to the established agreement for the procurement of new furniture.

Other out-of-the-box type procurement practices — for example, green public procurement or socially responsible procurement — have shown that taking the leap pays off, not only in financial terms but also by reducing environmental impact and improving lives across supply-chains through fair pay and good working conditions.

Public procurement becomes circular

In Malmö’s experience, while using the circular framework agreement instead of the established agreement for procurement of new furniture is a valuable tool, its implementation does not happen by default. To make its pilot a success, Malmö needed to address the challenge of behavioural change and set out to build a system in which buyers could use the new, circular framework agreement. As Emma Borjesson, Environmental Management Department of Malmö City, explained: “We want all buyers of the different departments, when furniture needs to be purchased, to check our internal options, like the second-hand market, first. In case they cannot find what they need, they would turn to the new supplier and purchase used or refurbished furniture.”

However, behavioural change in the context of procurement is a complex challenge that involves developing awareness, knowledge and capacity, as well as raising the level of ambition and personal buy-in by the sector. At the most basic level, implementation of innovative procurement practices requires that buyers and end-users, particularly in the case of framework contracts, are aware that the organisation is aiming to innovate new procurement practices. This can be a message delivered in the form of a wide-spread policy, in the form of unique requirements by a project manager, or even horizontally from other departments for example environmental or related to economic affairs.

The creation of the framework agreement in Malmö included the delivery of an information campaign with a series of events about the principles of the circular economy such as reuse, service models and remanufacturing. The events were open to all colleagues and aimed to show the benefits of circular economy by highlighting that circular procurement is not only about positive environmental impact but is also financially sound. In addition, awareness about the framework agreement could be increased, building on the existing in-house infrastructure of reuse and repair, such as an online second-hand marketplace, Malvin, as well as furniture repair services.

Acquiring the knowledge and capacity to carry out innovative practices is fundamental as circular procurement demands a different set of skills compared to traditional procurement. Buyers need thorough knowledge of the market readiness and characteristics of the product group with regards to potential circular aspects. They also need to become familiar with procurement procedures that are less often used, such as market consultation, procurement of innovations and pay-per-service contracts.

As part of the process of creating Malmö’s circular furniture framework agreement, the team behind the pilot project visited potential suppliers to discuss the circular model as well as the capacity of suppliers to cater to Malmö’s procurement needs. This format not only expanded knowledge through market engagement between buyers and suppliers but encouraged the team to go ahead with the circular approach.

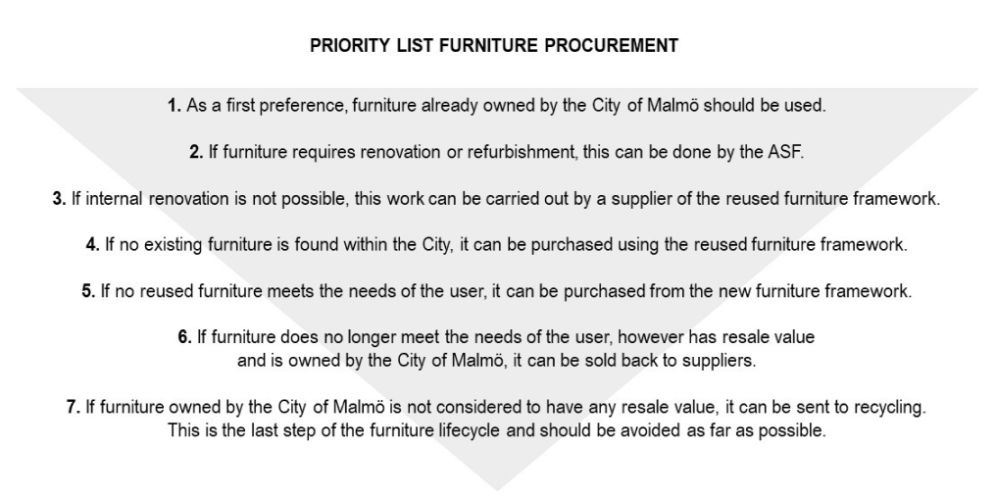

A ‘Priority List’ was developed alongside the creation of the new framework contract with the aim to guide circular procurement decision-making whenever a need for furniture arises. Using this list, a buyer should gain better knowledge about circular principles, such as refurbishment and reuse, before purchasing furniture items. The list was disseminated across departments as part of information about the new framework agreement.

As in all innovative processes, an array of setbacks and barriers are likely to arise for circular procurement. A level of ambition is therefore required from both project managers and buyers. Research has found that commitment to change and personal buy-in matters. This is particularly true when the commitment is based on an inherent belief in the benefits of the innovation practices. The mindset to constantly learn and to continue driving innovative processes even in the face of obstacles is what increases the chances of effective implementation of innovative procurement practices such as circular procurement. In Malmö, circular procurement is encouraged through strong support from management both in the procurement and environmental department, and for this particular project a Malmö procurement officer showed great enthusiasm for establishing circular furniture procurement, which contributed to the success of the project.

Katrin Stjernfeldt Jammeh, Mayor of the City of Malmö and Chair of Procura+ — a network of European public authorities for procurement innovation — commented: “As chair of Procura+, Malmö emphasises the leverage of using procurement as a strategic tool for achieving sustainable, circular and innovative economies. The city of Malmö is committed to taking a lead on implementing the shift towards a circular economy. The recent procurement for second-hand furniture is showcasing that implementation of circularity implies fundamental behaviour change. Circularity is not only about a product or service but about a shift in mindset. Cities can actively shape the transition by enabling staff to grow into this new way of how we consume and produce.”

The transition from cities based on linear systems to circular cities must include a change of mindset at different levels of decision-making. The example from Malmö in the context of the Circular PP project shows that public procurement offers an entry point to facilitate behaviour change within a city administration and holds the potential to grow beyond sectors and departments.

Lessons learned in this pilot project include the importance of starting with something simple, because circular economy and public procurement are complex. The interest of procurement staff should be harnessed, as it can drive the transition to a different way of procuring. Finally, circular economy is not only about different ways of contracting but about system change. Circular initiatives therefore need to include aspects of behaviour change to leverage not only a new design, but active use.

More findings from the Malmö project will be presented at the Baltic Circular Procurement Congress, taking place from 2–3 September 2020. Find out more about Malmö’s Sustainability Programme here.