One of the most analytically robust studies produced on ocean plastics, Breaking the Plastic Wave, published this week by The Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ, shows that we are well on our way to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s grim prediction that by 2050 there could be more plastic in the ocean than fish. But there is a solution: a circular economy for plastic.

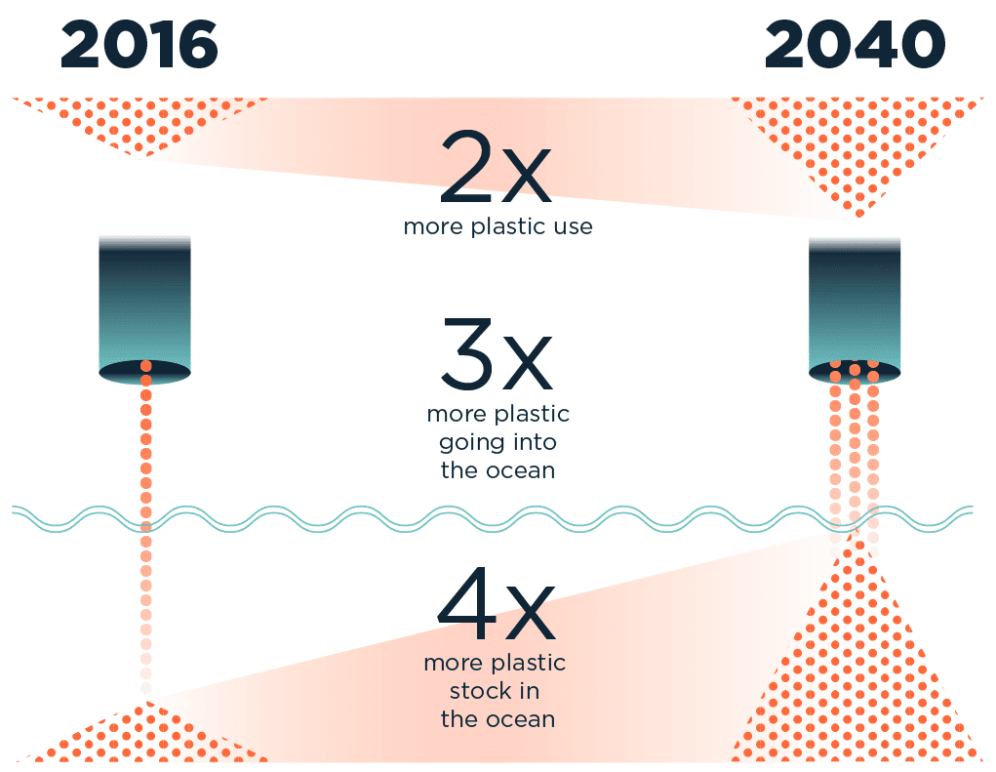

For decades, most efforts to tackle plastic waste and pollution have focused on waste management and environmental clean-ups. But the scale of the problem has only increased. Recent data shows that if we continue to make and use plastic in the ways we do now, by 2040 there will be twice as much plastic on the market, triple the amount of plastic entering the ocean each year, and four times the volume of plastic in the ocean.

Trying to stop this flow of plastic waste into the ocean is impossible with waste management and clean-ups alone — it is like trying to empty a bathtub with a thimble while the taps are on full blast. We need to ask ourselves: how can we stop plastic waste being produced in the first place?

To do this, instead of treating the symptoms of plastic waste and pollution, we need to address the cause, rethinking the whole plastic system.

System redesign

Today’s plastic industry is linear; materials are taken from the ground, products and packaging are made from them, and eventually they are thrown away as waste, often after only a very short period of use. Take a crisp packet for example. This complex, multilayered plastic is highly functional — it protects the crisps inside for months before they are eaten — but it cannot be used more than once and cannot be recycled. As a result, this plastic becomes waste. It is a direct result of decisions made at the packaging design stage. Plastics like this are destined for landfill or incineration from the moment they are made, and often end up in the environment.

But plastics are useful and valuable materials and the plastic system can be redesigned so that no plastic becomes waste or pollution. Since the problem starts long before plastic reaches our rivers, beaches and oceans, so must the solutions. The answer lies in a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. for plastic. Compared with business-as-usual, a comprehensive circular economy approach has the potential to reduce the annual volume of plastics entering our oceans by over 80%, generate savings of USD 200 billion per year, reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25%, and create 700,000 net additional jobs by 2040.

In order to achieve this, ongoing downstream efforts — collection, sorting and recycling — are needed, with investment directed towards infrastructure that ensures plastic stays in the economy and out of the environment. Over the next five years, at least USD 150 billion needs to be invested to realise this.

But downstream efforts alone will not be enough. Now we must focus our innovation efforts, like never before, upstream. This means rethinking not only the packaging, but the product and the system, so that packaging can either be eliminated, replaced with reusable packaging, or made recyclable or compostable. Rethinking what is put on the market in the first place is essential to tackling the problem. Instead of directing all our efforts toward dealing with a mountain of waste, upstream innovation aims to find ways to stop that waste being produced in the first place.

The innovators

Examples of upstream innovation are emerging across the plastics sector, as businesses recognise the benefits of a circular economy.

A standout example of packaging elimination through innovation comes from US-based Apeel, which is tackling the problem of single-use, non-recyclable shrink wrap packaging for fresh fruit and veg. They have produced an edible coating made from plant material that extends the shelf life of fresh products, eliminating the need for plastic wrapping without increasing food wastage. One cucumber supplier is expecting to eliminate more than 30 tonnes of shrink wrap annually with this solution. Apeel provides the coating in powdered form to packagers, who mix it with water and apply it to produce by either spray, brush or dip methods. It was recently announced that ASDA stores in the UK would begin carrying Apeel produce. USA retailer Kroger currently carries Apeel avocados, limes, and organic apples in their stores, and German retailer Edeka carries Apeel avocados, oranges, and mandarins. Apeel is safe to eat and completely compostable, meaning it will not contaminate organic waste streams.

In addition to eliminating packaging, innovation is needed to deliver products in new ways that allow for packaging to be reused many times over. Everdrop is an example of a company that has rethought its product to facilitate reusable packaging. The German start-up sells household cleaning products — but not as you might expect. They provide concentrated tablets that the customer mixes with water at home in reusable bottles. Removing water from products is a growing trend in reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification. innovation. It reduces shipping costs and carbon emissions compared to heavy, diluted products and the compact concentrated products lend themselves well to e-commerce. In Everdrop’s case, transport volume is reduced by 95%. As the tablets are dry, they are delivered in paper sachets, which are recyclable and compostable. The customer keeps the reusable bottle.

Another form of reuse is when a customer, instead of keeping the packaging, returns it to the business. One such business is Loop, a home delivery and pick-up service providing more than 200 products from well-known brands in premium reusable packaging. When a piece of packaging is empty, the customer puts it in a shipping bag, and then when the bag is full, schedules a pickup. The packaging is then sent back to be fully sterilised and refilled for another customer. The initial pilot in Paris and New York has served 10,000 customers and saw record sales in March and April 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Loop launched this month in the UK.

However, not all packaging can be eliminated or designed for reuse. Innovation efforts also need to focus on making single use packaging recyclable or compostable, or substituting for completely different material types that are recyclable or compostable, such as substituting plastic for paper.

US start-up JOI has reimagined its product in order to change its packaging needs and improve the recyclabilityrecyclabilityThe ease with which a material can be recycled in practice and at scale. of the packaging. JOI makes concentrated nut paste for making nut milk and other food items at home. Shifting from a liquid product to a solid changed the barrier requirements of the packaging, meaning it can now be made to be recycled. It also allows more servings per container, reducing the overall amount of packaging needed.

A challenge faced by makers of compostable packaging is making sure the packaging is actually composted in practice. BioPak in Australia tackled this by setting up their own collection and compostingcompostingMicrobial breakdown of organic matter in the presence of oxygen. service. On top of the compostable serveware they produce, food scraps too can be diverted from landfill. More than 200 businesses now use the service to compost their food waste and packaging. Since launching in 2017, the service has diverted in excess of 1,500 tonnes of compostable packaging and food scraps from landfill and created 105,000 bags of compost.

An example of material substitution is Flexi-Hex, a global producer of protective transport packaging. They have developed a honeycomb-design, flexible cardboard as an alternative to bubble-wrap, tape and foamed materials. This substitutes non-recyclable materials that would end up as waste for packaging that is fully recyclable and compostable. It is also made from 100% recycled paper pulp.

Stemming the flow

These innovators have shown that it is possible to design out packaging waste. There are quick wins to be had through direct elimination of unnecessary packaging, followed by more innovative approaches that rethink the product and system so that the packaging is no longer needed. Then there is the huge potential of reuse, and then for the single use packaging that cannot be eliminated entirely, there is recycling and composting.

However, as the Breaking the Plastic Wave study shows, even if the plastics system utilises all known solutions to plastic waste at maximum realistic speed and scale, it would still result in more than 150 million tonnes being landfilled, incinerated or mismanaged every year by 2040 — including 5 million tones ending up in the sea. This would constitute an 80% improvement on business-as-usual, but still sees a significant volume of waste entering the environment. Therefore, on top of innovation towards known solutions, we must innovate towards new business models, product design, materials, technologies, and collection systems.

In tackling the global plastic waste crisis, there is no time to lose. Breaking the Plastic Wave shows that a delay of just five years would result in an additional 80 million tonnes of plastic entering our oceans between now and 2040 — equivalent to 13,000 bottles per second for the next 20 years. Delay today could lead to disaster tomorrow.

We know what needs to be done. The solution lies in taking urgent, ambitious, and coordinated action across the entire plastics system with a clear emphasis on stemming the flow at its source.

Find more case studies of upstream innovation in the Foundation's Upstream Innovation Guide.