Changing our food system is one of the most impactful things we can do to address climate change, create healthy cities, and rebuild biodiversity. The current food system has fuelled urbanisation, economic development, and supported a fast-growing population. However, this has come at an enormous cost to society and the environment.

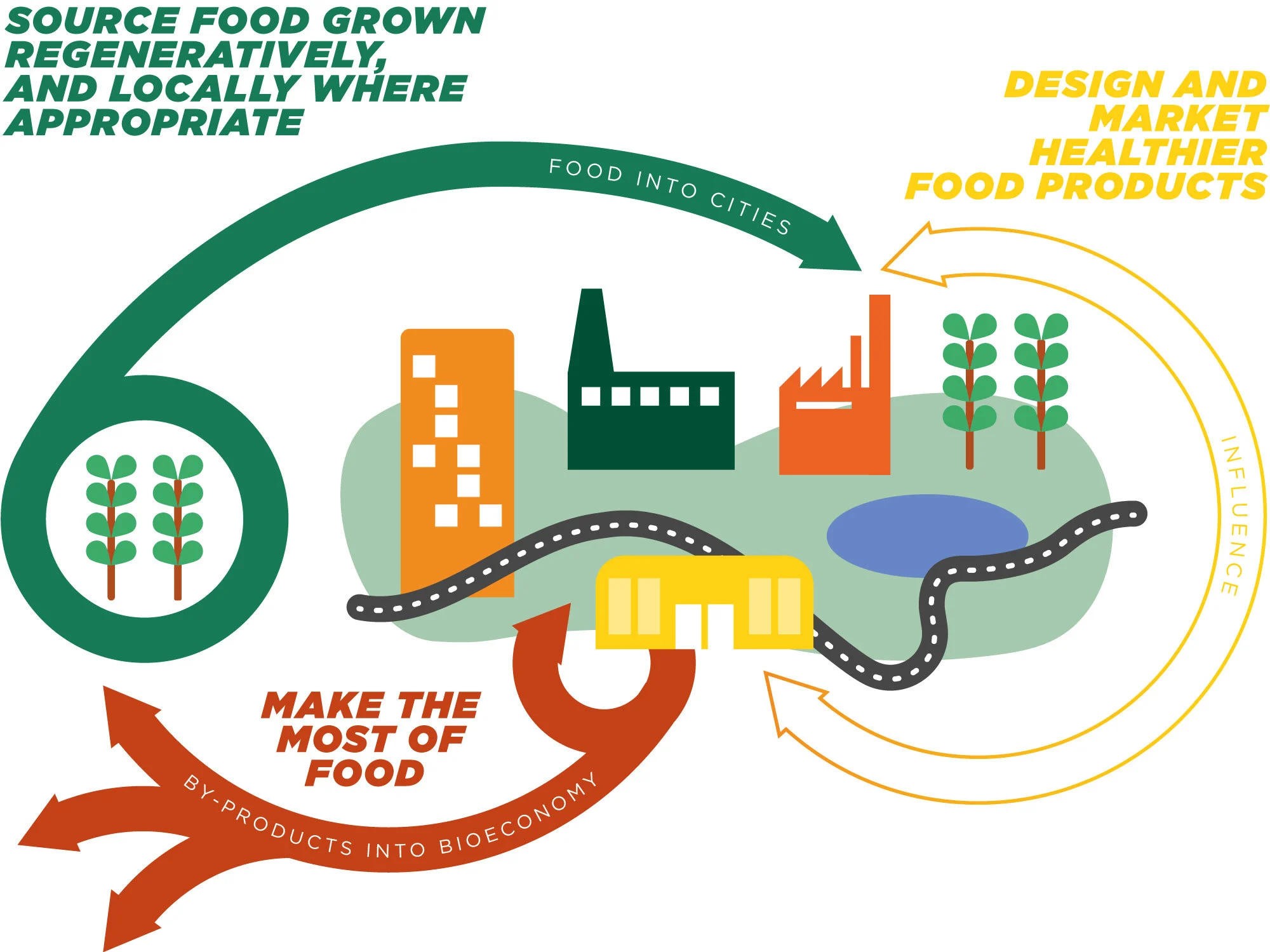

This learning path begins by examining the true cost of the current approach to food production. It then explores the catalytic role of cities and how they can seize the opportunity to change the global food system through three ambitions:

Sourcing food grown regeneratively, and locally where appropriate

Designing and marketing healthier food products

Making the most of food

Finally, the potential benefits of realising these ambitions are presented.

The linear food system is ripe for disruption

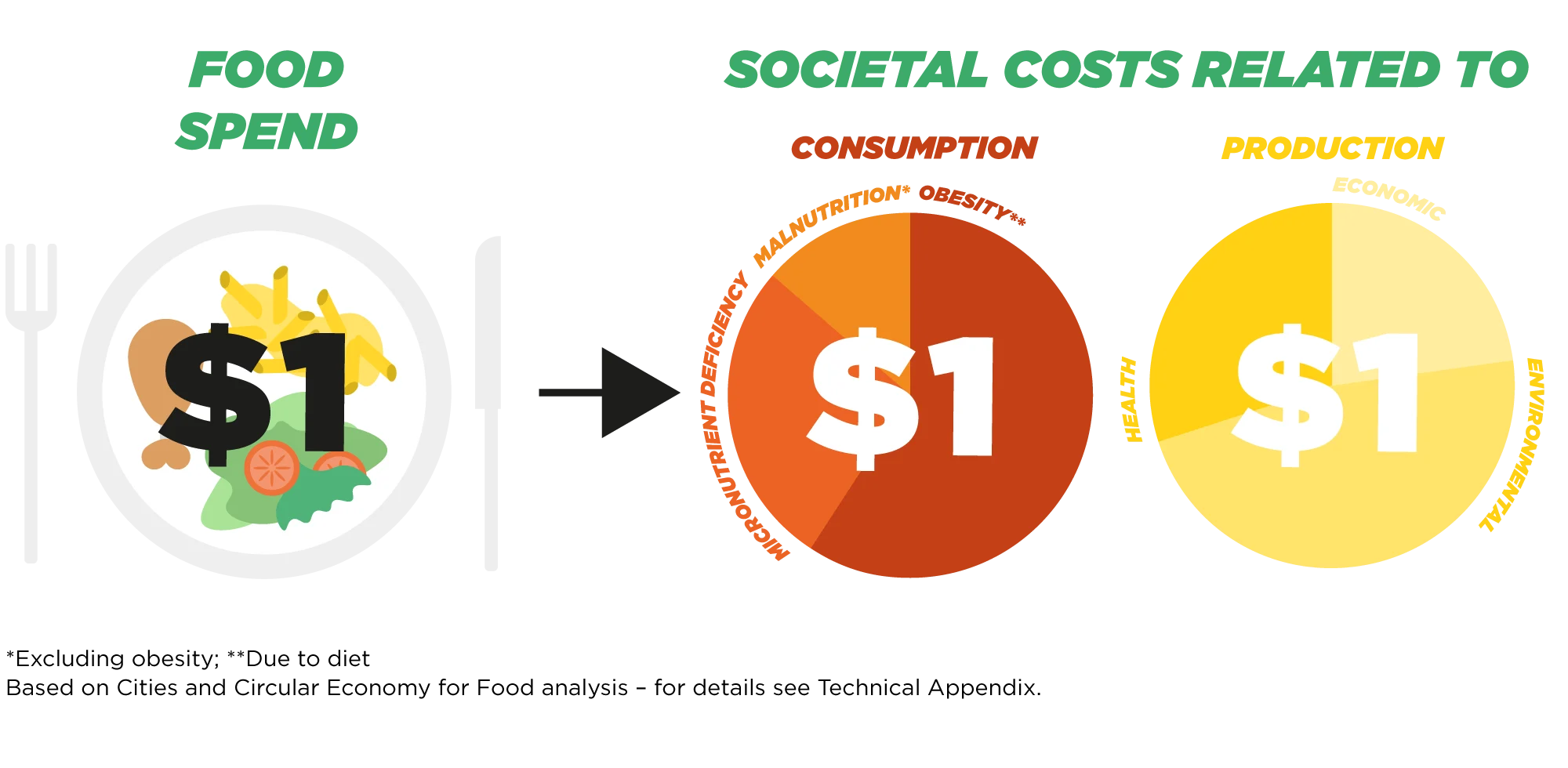

For every dollar spent on food, society pays two dollars in health, environmental, and economic costs.

The current food system has supported a fast-growing population and fuelled economic development and urbanisation. Yet, these productivity gains have come at a cost, and today’s model is not fit to meet tomorrow’s longer term needs.

Half these costs – totalling USD 5.7 trillion each year globally – are due to the way food is produced. They are a direct result of the ‘linear’ nature of modern food production, which extracts finite resources, is wasteful and polluting, and harms natural systems.

Intensive agricultural practices are also a significant contributor to the 39 million hectares of soil that are degraded each year globally (an area the size of Zimbabwe), and places demand on approximately 70% of global freshwater.

The linear system is wasteful

The equivalent of six garbage trucks full of edible food is lost or wasted every second.

In cities, less than 2% of the nutrients in food by-products and human waste produced is recovered and put to good use. Instead, these nutrients are destined for landfill or incineration, or worse, released untreated.

Perhaps most surprisingly, even when apparently making healthy food choices, people’s health is still being harmed by the way we produce food and deal with its by-products. By 2050, around 5 million lives a year – twice as many as the current obesity toll – could be lost as a result of current food production processes. Among the harmful impacts of such methods are diseases caused by air pollution and water contamination, health consequences of pesticide use, and increased antimicrobial resistance. Some of the principal causes are overuse of fertilisers, excessive reliance on antibiotics in animals, and untreated human waste.

But it doesn’t have to be this way if we begin to look beyond the current ‘take, make, and waste’ industrial model.

Circular economy for food

A circular economy for food mimics natural systems of regeneration so that waste does not exist, but is instead feedstock for another cycle.

In a circular economy, organic resources such as those from food by-products, are free from contaminants and can safely be returned to the soil in the form of organic fertiliser. Some of these by-products can provide additional value before this happens by creating new food products, fabrics for the fashion industry, or as sources of bioenergy. These cycles regenerate living systems, such as soil, which provide renewable resources, and support biodiversity.

Some businesses are operating in a way that helps regenerate natural systems. The Balbo Group began work in 1986 to change their mode of operating. In the video below, Leontino Balbo describes the positive impact this has had on the long term health of their farm’s environment - and the company.

Creating such a systemic shift will require investments of both time and funding, but without either, our agricultural systems are on a trajectory to suffer in the long-term, which will impact all of us.

Take a look here at our article on regenerative food production.

Pause for thought

Why are cities so important for creating change?

Opportunity for cities

Cities, and everyone within them, have a unique opportunity to spark a transformation towards a circular economy for food.

Half of the world’s population currently lives in cities. This number is expected to grow to 68% by 2050 at which stage 80% of the world’s food will be eaten within cities.

Consumption of food per person tends to be greater due to urban citizens earning higher average incomes than rural citizens. Yet, the high proportion of the food that flows into cities is processed or consumed in a way that creates organic waste in the form of discarded food, by-products or sewage.

The close proximity of citizens, retailers, and service providers (40% of cropland is within 20km of cities), makes new business models possible. Demand power, due to the sheer volumes of food eaten, means that city businesses and governments are ideally placed to influence the type of food that enters a city, and how and where it is produced.

Cities as catalysts in changing the food system

1) Source food grown regeneratively, and locally where appropriate

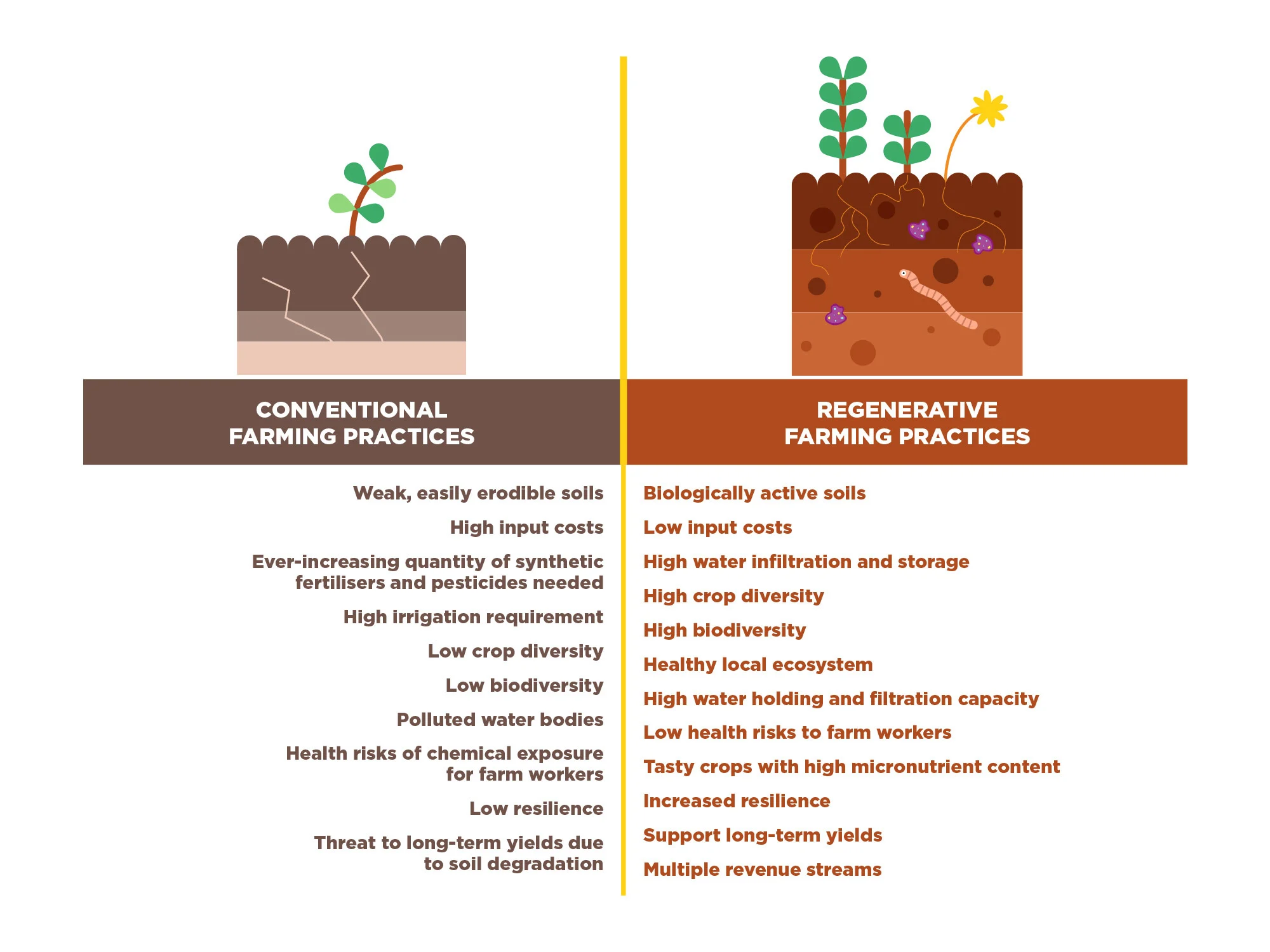

Regenerative approaches to food production will ensure the food that enters cities is cultivated in a way that enhances rather than degrades the environment. In this context, regenerative food production means to encompass production techniques that improve the overall health of the local ecosystem.

2) Make the most of food

Cities can play an important role in sparking the shift to a fundamentally different food system. A system which moves beyond simply reducing avoidable food waste to one that designs out the concept of ‘waste’ altogether.

3) Design and market healthier food products

In a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature., food products are designed to be healthy, right through from production to nutrition. New innovations, products, and recipes can play their part in designing out waste. Marketing can position delicious and healthy products as easy and accessible choices for people on a daily basis. Food brands, retailers, restaurants, schools, hospitals, and other providers can ‘guide’ our food preferences and habits to support regenerative food systems.

Glossary of terms

Agroecology

An integrated approach that simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of food and agricultural systems. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

Rotational grazing

Involves frequent stock movements through a variety of different fields and pastures to reduce grass wastage and provide a rest for the grass. (Farm Advisory Service)

Agroforestry

A land management approach involving the planting of trees on farms to help farmers produce healthier soil, higher yields, and create homes for wildlife. (Soil Association)

Conservation agriculture

A sustainable and resource saving agriculture production system, which involves practices adapted to local conditions to prevent land from erosion and degradation, and improve quality and biodiversity. (Conservation Agriculture Association for the United Kingdom)

Permaculture

Permaculture integrates land, resources, people, and the environment through mutually beneficial synergies – imitating the no waste, closed loop systems seen in diverse natural systems. (Permaculture Research Institute)

Bioenergy

Energy that is derived from recently living organic materials known as biomass, which can be used to produce transportation fuels, heat, electricity, and products. (United States Department of Energy)

Bioeconomy

The parts of the economy that use renewable biological resources from land and sea – such as crops, forests, fish, animals, and microorganisms – to produce food, materials, and energy.

Hydroponic

Hydroponics is the science of growing plants without using soil, by feeding them on mineral nutrient salts dissolved in water. (Royal Horticultural Society)

Aquaculture

The breeding, rearing, and harvesting of fish, shellfish, plants, algae, and other organisms in all types of water environments. (National Ocean Service)

Natural capital

The world’s stocks of natural assets which include geology, soil, air, water, and all living things. It is from this natural capital that humans derive a wide range of services, often called ecosystem services, which make human life possible. (World Forum on Natural Capital)

Sourcing food grown regeneratively

Regenerative food production means employing techniques that replenish and improve the overall health of the local ecosystem.

It supports natural systems, rebuilding and enhancing ecosystems, while preserving air and water quality.

Examples of regenerative practices include shifting from synthetic to organic fertilisers, employing crop rotation, and using greater crop variation to promote biodiversity. Farming types such as agroecology, rotational grazing, agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and permaculture, all fall under this definition. Regenerative practices support the development of healthy soils, which can result in foods with improved taste and micronutrient content.

Listen to Leontino Balbo Jr. In 1986, he began experimenting with a new approach that he believed could increase crop yields, reduce pest numbers, restore natural capital, and reduce reliance on natural resources.

Local food production

Can cities produce their own food?

Opinions vary on the potential for cities to act as food production hubs - and the benefits of doing so. Alone, urban farming systems, such as those that combine indoor aquaculture with hydroponic vegetable production, can only provide a limited amount of nutrition required for human health.

Cities can, however, source a large share of food from their surrounding areas: 40% of the world’s cropland, referred to as peri-urban areas, is located within 20 km of cities.

By understanding their existing peri-urban production, cities can demand food that is not only grown regeneratively, but also locally - when it makes sense - and support diversification of crops by selecting varieties best fitting local conditions, thereby building resilience.

Listen to Morten Rosse who describes the potential for the regeneration of peri-urban land in developing countries.

Watch Hamilton Henrique tell a story of food revolution.

Reconnecting cities with food and farmers

Supporting regenerative practices that benefit local environments.

Rather than planning to source all food from peri-urban areas, cities should aim to form resilient food supplies that rely on a diverse set of local, regional, and global sources, according to where food types grow best.

Robyn Metcalfe, Lecturer and Research Scholar at the University of Texas at Austin puts it this way:

Local sourcing can play a significant role in supporting the development of a distributed and regenerative agricultural system. It allows cities to increase the resilience of their food supply by relying on a more diverse range of suppliers (local and global).

By reconnecting city dwellers with food and the farmers who grow it, the likelihood increases that people will demand food grown using regenerative practices that benefit the local environment and their own health.

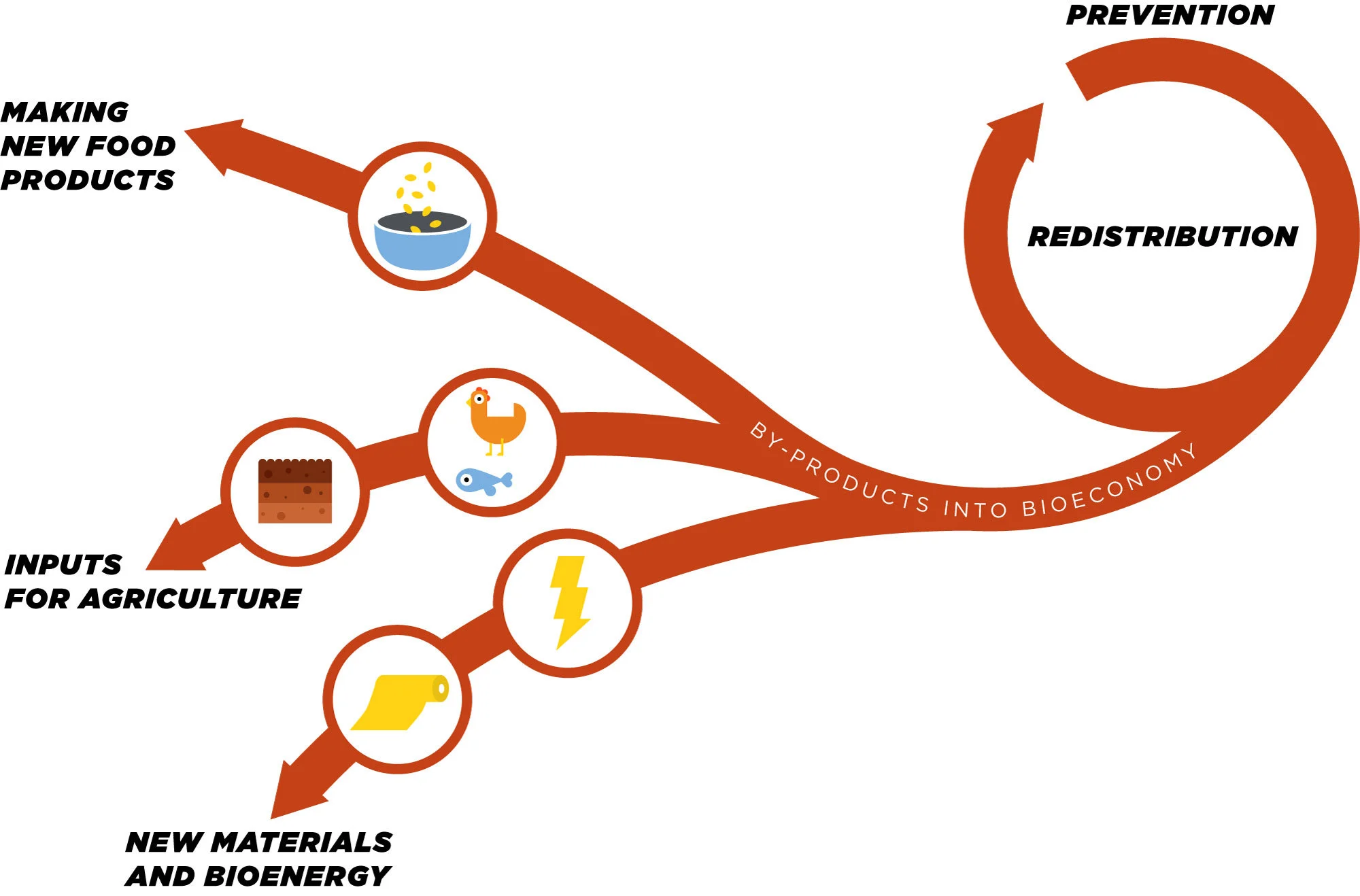

Making the most of food

Instead of simply reducing avoidable food waste, why not design out the concept of ‘waste’ altogether?

Currently, a third of all food produced globally – worth USD 1 trillion – is thrown away each year. This represents a huge loss of nutrients and a major cause of environmental issues. Yet, still, 10% of the global population continues to go hungry.

In a circular economy, food is designed to cycle, so the by-products from one enterprise provides input for the next. Cities can make the most of food by redistributing surplus edible food, while turning the remaining inedible by-products into new products, ranging from organic fertilisers for regenerative peri-urban farming, to biomaterials, medicine, and bioenergy.

Rather than a final destination for food, cities can become centres where food by-products are transformed, through emerging technologies and innovations, into a broad array of valuable materials. These could range from organic fertilisers and biomaterials, to medicine and bioenergy, thereby driving new revenue streams in a thriving bioeconomy. Besides ensuring that edible food is distributed to citizens, the choice of the ‘best’ option depends on the local context, including the type of available feedstock, and the demands for particular products in that specific region.

Preventing food waste

Rather than reduce, let’s prevent food waste at the source.

Cities can initiate a range of food waste prevention interventions. From better matching supply with fluctuating demand for different food types, to discounting soon-to-expire products, and using overripe produce for in-store food outlets, retailers can reduce their food waste. Waste prevention efforts are also being addressed by organisations such as FoodShift and Feedback.

Cities can transform collected organic materials to drive regenerative peri-urban food production. Currently in cities, the most common management processes for organic materials are composting, anaerobic digestion, and wastewater treatment.

Converting organic waste into a source of value begins with effective collection systems and pure waste streams. New technology, supporting policy frameworks, and community engagement can rapidly transform collection systems and increase organic waste collection rates. While all countries can benefit from improved collection systems, emerging economies are especially well-positioned due to their high shares of organic waste and early stages infrastructure.

Explore more: Food brands can use ‘ugly’ fruits and vegetables as ingredients for food products. Rubies in the Rubble have created a profitable new condiment brand using some of the 30% of perfectly edible food that is thrown away.

Designing and marketing healthier food products

Food products must be designed through a system that provides healthy production as well as nutrition.

Food brands, retailers, chefs, food businesses, schools, hospitals, and other providers have a major influence on what we eat - a significant proportion of our food has been designed in some way by these organisations. Food designers have the power to ensure their food products, recipes, and menus are healthy to both people and natural systems and marketing activities can then be shaped to make these products attractive to people.

In a circular economy, food products derive from healthy production to provide healthy nutrition. Similarly, the packaging that preserves food can be made from materials that compost as safely and easily as the food it contains. In addition, the food we eat should originate from a rich diversity of sources (The world relies on just three crops for more than 50% of its plant derived protein).

Food loss and waste can be designed out along the entire food supply chain. Designers can develop products and recipes that use food by-products as ingredients, and those which, by avoiding certain additives, can be safely returned to the soil or used in other ways.

Take a look at The Big Food Redesign Challenge, which aims to catalyse and inspire the food industry to build a better food system based on the principles of a circular economy.

Healthier food products

Design better food options

Blending mushrooms into burger patties adds delicious ‘umami’ and Vitamin D into the mix, and means fewer calories. Mushrooms can be grown on spent coffee beans, which combined with a lower meat content, can enhance your health and that of the planet.

Healthy for people and planet

Yuba – also known as bean curd robes – is the skin collected from the tofu making process. Layered and bound together, yuba can be made into an imitation chicken breast – it even gets a crispy chicken-like skin when you pan fry the outside.

Using by-products

Pasta manufacturer Barilla have teamed up with paper company Favini to produce a line of quality packaging and paper products called ‘Cartacrusca’ using the by-products of pasta production.

Regenerating nature

Designers need to create products with ingredients that are, regardless of their source (animal or vegetable), produced regeneratively. Where possible, they need to be obtained locally and therefore seasonally, to be safely used as inputs for new uses. It is these processes that will contribute to a thriving bioeconomy.

The benefits

Macroeconomic benefits

Achieving these three ambitions would allow cities to move from passive consumers to active catalysts of change, and generate annual benefits worth USD 2.7 trillion by 2050, that can be enjoyed by people around the world.

Environmental benefits

Avoiding the degradation of 15 million hectares of arable land per year; and saving 450 trillion litres of fresh water.

Health benefits

Health benefits include lowering the health costs associated with pesticide use by USD 550 billion, as well as significant reductions of antimicrobial resistance, air pollution, water contamination, and foodborne diseases.

Economic opportunities

Cities can also unlock an economic opportunity upwards of USD 700 billion by reducing edible food waste, using nitrogen and phosphorus from food by-products, and organic materials for new cycles.

Business opportunities

From producers and brands to processors and retailers, businesses across the food value chain can tap into high-growth sectors, such as biomaterials or delicious plant based protein products.

A collaborative effort

Using the catalytic potential of cities to spark change can be a powerful addition to the efforts needed to transform our relationship with food.

Mobilising these three ambitions and realising the vision at scale will require a global systems-level change. It will take major effort and contributions from all the main urban food system actors, working together collaboratively in an unprecedented way.

Here are just some of the diverse food system stakeholders who will need to work together to create the shift to a new, healthy, food system.

Creating a new food system

Three ambitions, multiple benefits.

The challenges of the global food system can sometimes seem daunting in their breadth and sheer complexity. But there are tremendous opportunities available to businesses and governments in cities to take a long-term view of the future of food and catalyse a fundamental shift in the system.

As with all complex situations, the three ambitions need to be pursued in a way that recognises and acts upon their interdependence both with each other, and with complementary initiatives being developed by other organisations. If realised, the circular economy approach could yield huge benefits to city economies, human health, and the environment, as well as helping to achieve many of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The challenge for all of the city food players around the world is to seize the chance to get behind a common vision of a truly healthy and regenerative food economy and then make it happen – at scale and at pace.

Related videos

-----------------------

Funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation