Whether you like your coffee strong, smooth, sweet or foamy, the way that the coffee is grown and produced matters as much as how it is brewed. Circular economy strategies can ensure coffee is not only enjoyable but good for nature too.

Think of your perfect cup of coffee. What does it look like, smell like, taste like? Where do you make it, where do you sit (or stand) to drink it, and how does it make you feel once you have? Mine is short and silky smooth, taken at 09:15 on the dot with emails in one tab and a long-read or five in the others – it tastes of pepper, pomegranate, and productivity. Yours will be different, of course; coffee consumption is as much a personal experience as coffee science is an artform. The process of drinking coffee often makes me ponder. One recent morning at approximately 09:23, I found myself pondering what a ‘perfect’ cup of coffee might look like if we think about not only our personal preferences but also the necessity to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss (something else which is often on my mind as I consume my morning coffee).

Coffee that creates a positive impact

My daily dose leaves me feeling regenerated, but does it help regenerate nature? The energy boost it bestows upon me is welcome (and needed) but what about the energy-related emissions of its processing and packaging? Tamping techniques, I am told, help extract maximum flavour, but what is the impact of its seed extraction on natural systems? Some like their coffee strong: but whatever the reading on the refractometer, the strength markers we should really be paying attention to are the climate and disease resilience of the origin crop and the stability of its global supply chain. Ultimately, the way that the coffee is grown and produced matters as much as how it is brewed. Likewise, we must ensure that the coffee we drink has a positive impact on the people and communities who grow, harvest, and prepare it – not just consumers.

The circular economy can keep us within planetary boundaries

I like a spot of satisfyingly-swirling latte art as much as the next coffee geek. I’m also a fan of iconic industry graphics, so I can appreciate the visual appeal of the World Coffee Research (WCR) colourful coffee taster’s flavour wheel. But as I get lost in its segments, I can’t help but notice its similarity to another famous framework – not of coffee science, but of climate science. When we map the impact of global coffee production against the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s Planetary Boundaries model, the need to change from a mindset of taste preferences and cost considerations to one that also considers the environment is clear. Coffee that is grown in a synthetic fertiliser and pesticide dependent conventional agricultural system – and later produced and packaged in the highly extractive and emissions heavy landscape of a linear economylinear economyAn economy in which finite resources are extracted to make products that are used - generally not to their full potential - and then thrown away ('take-make-waste'). – contributes to the breach of multiple planetary boundaries. Each threatens the stability of our earth systems by pushing us closer to climate tipping points.

Underpinned by an urgent transition to renewable energyrenewable energyEnergy derived from resources that are not depleted on timescales relevant to the economy, i.e. not geological timescales., the circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. can help us tackle climate change, biodiversity loss, waste and pollution — and, by consequence, stay within planetary boundaries. A circular economy eliminates waste and pollution, keeps products and materials in circulation, and regenerates nature. It is a system of environmental-economic solutions which can be seen through the story of coffee.

Coffee drinking is ritualistic as well as restorative

Drinking a coffee is a momentary pause in a work-wild world that is never a waste of time. But these pauses can often involve wastefulness — of single-use coffee cups, sugar sachets, and stirrers. This needs to change. In our current linear economy, the proliferation of waste — both material and structural — has significant consequences for the ongoing nature of our global interconnected polycrisis.

The good news is, across the global coffee industry, circular economy actions are beginning to take hold. In this vital work to decouple economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, the principles of circular design have helped to establish home-compostable capsules, city-wide reusable cup systems, and pay-per-use coffee machines. In recent years, coffee waste has been imaginatively repurposed, with recycled grounds used to create stylish sneakers, post-use dregs turned into natural fashion fibres, and dried silverskin chaff into car parts.

Nature can be our greatest ally

Each of these examples shows us that a better future for business, society, and the natural world is possible. But we need to go further still. In a circular economy, the regeneration of nature is essential if we are to not only prevent additional harm but provide the conditions for natural systems to begin to build back. The aim should be to do more good rather than less bad. The global food system is a great place to start. When it comes to coffee, helping farmers to transition to regenerative agriculture can have powerful benefits.

Coffee aficionados care about space; from the recommended clearance between the machine and kitchen wall to the perfect optimisation of headspace between coffee and filter basket. Outside of the home, rising demand for coffee means that this soft commodity currently contributes to global deforestation through large-scale land clearance, destroying biodiversity and releasing climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions. Such impacts are, unfortunately, typical of conventional agriculture — the same is true of cotton, corn, and cacao. Since rising global temperatures will reduce suitable growing areas by up to 50%, finding a solution is essential.

In a regenerative agricultural system, the spatial footprint of these shade-loving plants is maximised. Depending on the region, this might mean adding macadamia trees or bananas into the mix — called intercropping — or planting fast-growing native forest trees to aid cooling. As well as the planetary benefits (dense intercropping helps to fix broken biogeochemical cycles, reducing both pollution and emissions) this method helps farmers diversify output and income towards greater long-term security and crop yields.

The future of coffee farming is regenerative

This is just one way in which regenerative agriculture can help to secure the future of coffee farming — and the future security of our food systems more widely. Others are connected by water. In a cup, water-based choices — filtered, boiled, or distilled — bring subtle differences in taste and tone. At scale, coffee’s relationship with water is more meaningful, currently contributing to global freshwater scarcity. In 2019, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization said that a single cup of coffee requires 140 litres of water to grow, process, and transport.

Rather than debate the optimum conditions of our favourite morning drink, therefore, we should reframe our focus to how it can help protect precious natural resources. By increasing the filtration and retention capacity of the soil, agricultural practices with regenerative outcomes help to reduce demand for — and reliance on — freshwater reserves. The water story continues.

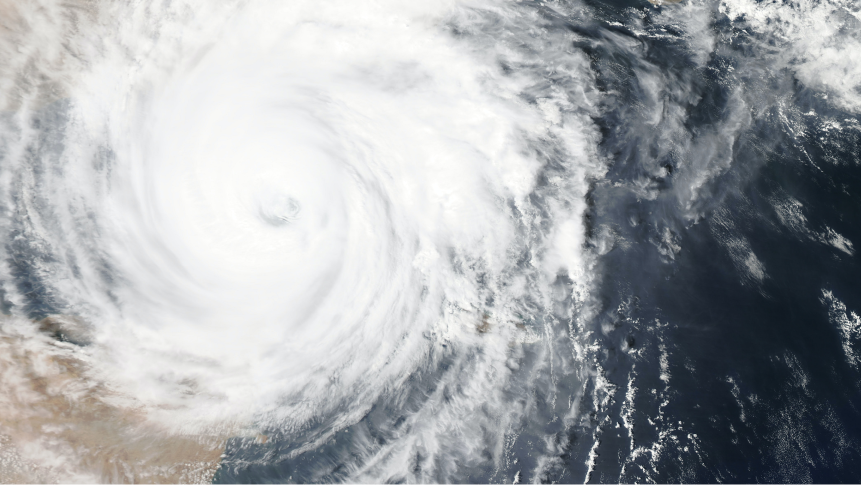

On the ground, climate change-related extreme weather events — both flooding and drought — stunt growth, impacting yield and farmer profitability. Too much rain causes mould; too little means unproductive fruit. As a mitigation strategy, a circular economy helps to reduce the emissions that are causing these unpredictable and volatile weather patterns as part of wider climate action.

Global climate action remains essential

Though temperature is another hotly contested topic in coffee-making circles, coffee doesn’t just react to water temperature in a cup. As a climate-sensitive crop, even minor temperature rises affect yield, aroma, flavour — and susceptibility to disease. My favourite mug is an Irish pottery number complete with tactile imperfections. But as I sip from its textured rim, I am reminded not only of the Wild Atlantic Way but of coffee leaf rust. The pebbly coating, fine orange dust, and flecked markings are characteristic of this foliar fungal infection afflicting coffee plants worldwide and threatening the livelihoods of millions who rely on them. It is being exacerbated by the heat and humidity of climate change. By protecting plants from wind activated spore-dispersal, the risk of disease is reduced in a regenerative agricultural system. Nevertheless, global climate action is urgently required.

The challenges ahead are interconnected

In my trawl of coffee related content, I have found sites dedicated to the perfect grind: coarse, medium, fine, and everything in between. Without downplaying the sensory stimulus that such detail brings, I am struck by the parallel consistency of another kind of matter: soil. In conventional agricultural systems, soil health is degraded through chemical input, disturbed through excessive tillage, stripped of biodiversity, microorganisms, and nutrients. But grown as part of a regenerative system, its fertility, nutrient density, moisture retention, structure, stability, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity are all strengthened.

The scale and complexity of these interconnected global challenges — not to mention our complicity in their construction — seems a lot to consider on a weekday morning. But, then again, what is a coffee break if not a little time and space to face up to the big questions, consider the root causes of shared problems, and give us the confidence to take steps towards their solutions.

From coffee to chickpeas: many of the world’s staple crops can be farmed and produced in ways that have regenerative outcomes for nature as part of a circular economy for food. Find out more.

This article was first published on The Positive Cup Hub on the 8th of June 2023.