Our relationship with plastic needs rethinking.

Plastics are versatile materials, but the way we use them is incredibly wasteful. We take oil and gas from the earth to make plastic products that are often designed to be used only once, and then we throw them away. This is what we call a linear take-make-waste model.

Year on year, millions of tonnes of plastic, worth billions of dollars, ends up in landfills, is burned, or leaked into the environment. A staggering 8 million tonnes leaks into the ocean every year — and that number is rising. If we don't rethink its use, there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish (by weight) by 2050.

No-one wants to be in this position. Is it possible to rethink the way we design, use, and reusereuseThe repeated use of a product or component for its intended purpose without significant modification. plastics to create a circular economycircular economyA systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. It is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. for plastic?

The linear plastic system

The use of plastics has increased twentyfold in the past 50 years. While the material has many benefits, we now know there are negative consequences if it becomes waste or pollution. Documentaries such as Blue Planet II, showing the impact of plastic pollution on wildlife around the world, have shocked and spurred a public backlash against the material.

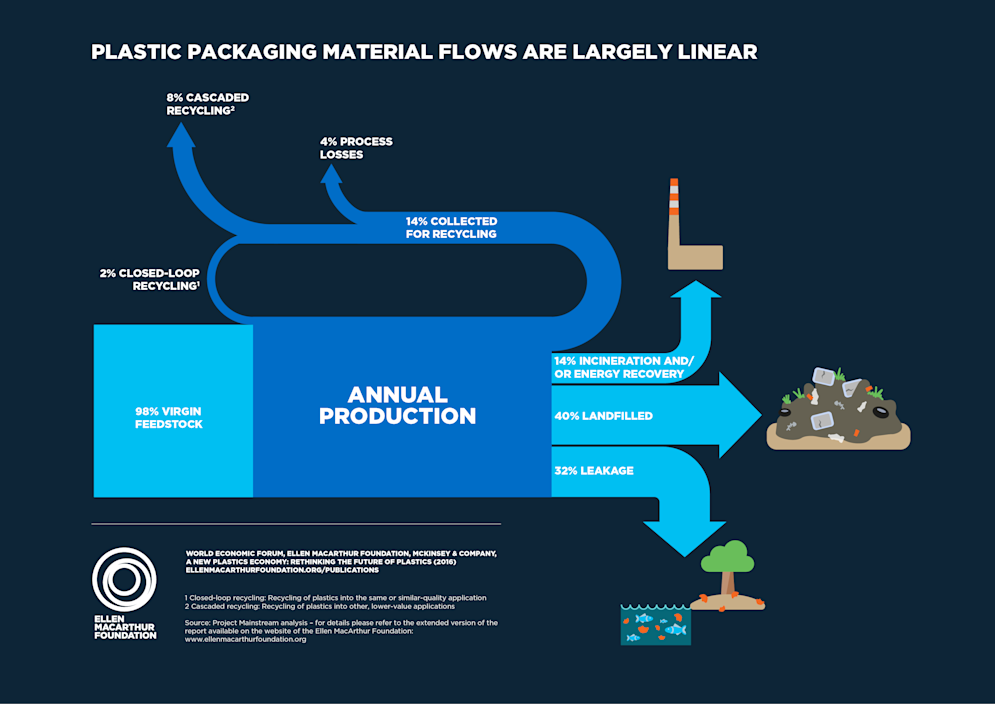

In 2016, the Foundation published a report which showed that most plastic packaging is used only once, and only 14% is collected for recycling. 95% of the value of plastic packaging material, worth USD 80-120 billion annually, is lost to the economy.

In our second report on plastics, published in 2017 - with our partners, we showed that without fundamental redesign and innovation, about 30% of plastic packaging will never be reused or recycled.

So how can we design a circular economy for plastic, in which it never becomes waste or pollution?

More beach clean-ups?

Beach clean-ups are needed to clean up the waste already in our environment, but they are far from enough. Even if we manage to clean up the current plastic in the environment, more plastic leaks into it every day. Every minute, one garbage truck of plastic waste enters the world’s oceans. We need to stop plastic leaking into the environment.

Ban all plastic and replace it with another material, such as glass, paper or aluminium?

In some cases, banning plastics can be a solution, but substitution of plastic with other materials can lead to significant negative, unintended consequences, such as increased carbon emissions, water use, and food waste. In every case, we must take a holistic approach, looking at the whole system in which a material is used, from sourcing and production to use and after use.

SOLUTION: Redesign the entire plastics system

We need a systemic approach to create a system that works in practice, without loss of economic value and no plastic waste or pollution. We need to rethink the way we make, use, and reuse plastics, essentially redesigning the system in which the material is used.

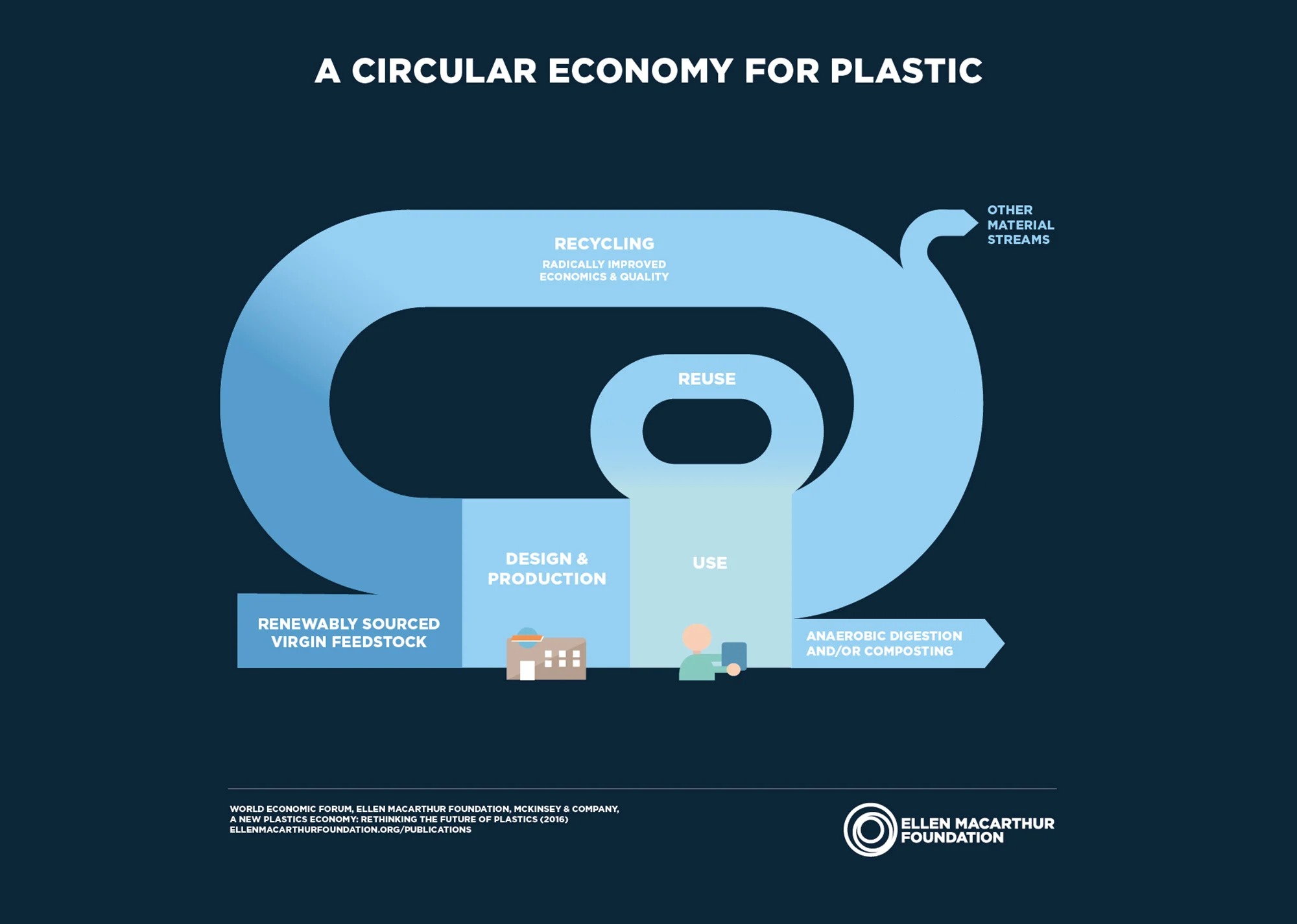

A circular economy for plastic

The circular economy is an economic system in which materials are designed to be used, not used up. From the outset, products and the systems they sit within should be designed to ensure no materials are lost, no toxins are leaked, and the maximum use is achieved from every process, material, and component. If applied correctly, the circular economy benefits society, the environment, and the economy.

All packaging should be designed to fit within a system, whether a reuse, recycling or compostingcompostingMicrobial breakdown of organic matter in the presence of oxygen. system.

Eliminate the plastics we don’t need.

Plastic brings many benefits. At the same time, there are some problematic items on the market that need to be eliminated to achieve a circular economy, and sometimes, plastic packaging can be avoided altogether while maintaining utility.

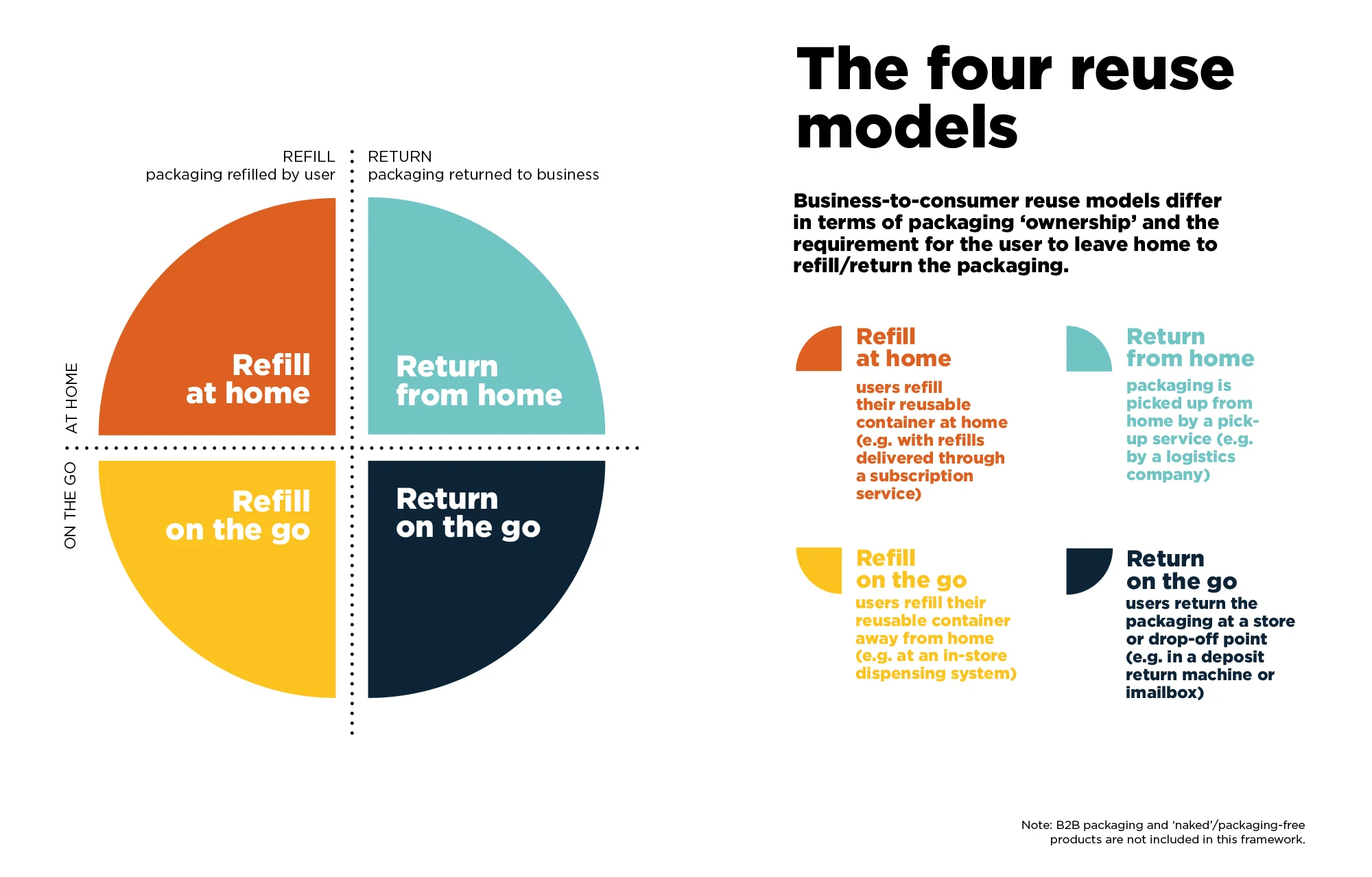

While improving recycling is crucial, we cannot recyclerecycleTransform a product or component into its basic materials or substances and reprocessing them into new materials. our way out of the plastic issues we currently face. Wherever relevant, reuse business models should be explored as a preferred solution (or ‘inner loop’ in circular economy terms), reducing the need for single-use plastic packaging. Reuse models, which provide an economically attractive opportunity for at least 20% of plastic packaging, need to be implemented in practice and at scale.

Innovate to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable, or compostable.

This requires a combination of redesign and innovation in business models, materials, packaging design, and reprocessing technologies.

Compostable plastic packaging is not a blanket solution, but rather one for specific, targeted applications, because an effective collection and composting infrastructure is essential but often not in place.

Circulate all the plastic items we use to keep them in the economy and out of the environment.

No plastic should end up in the environment. Landfill, incineration, and waste-to-energy are not long term solutions that support a circular economy.

Governments are essential in setting up effective collection infrastructure, facilitating the establishment of related self-sustaining funding mechanisms, and providing an enabling regulatory and policy landscape.

Businesses producing and/or selling packaging have a responsibility beyond the design and use of their packaging, which includes contributing towards it being collected and reused, recycled, or composted in practice.

What is the vision for a circular economy for plastic?

The vision for a circular economy for plastic has six key points:

Elimination of problematic or unnecessary plastic packaging through redesign, innovation, and new delivery models is a priority

Reuse models are applied where relevant, reducing the need for single-use packaging

All plastic packaging is 100% reusable, recyclable, or compostable

All plastic packaging is reused, recycled, or composted in practice

The use of plastic is fully decoupled from the consumption of finite resources

All plastic packaging is free of hazardous chemicals, and the health, safety, and rights of all people involved are respected

Elimination, reuse, and material circulation

In a new plastics economy, plastic never becomes waste or pollution. Three actions are required to achieve this vision and create a circular economy for plastic. Eliminate all problematic and unnecessary plastic items. Innovate to ensure that the plastics we do need are reusable, recyclable, or compostable. Circulate all the plastic items we use to keep them in the economy and out of the environment.

Without elimination, achieving a circular economy for plastic will not be possible. With the demand for plastic packaging set to double over the coming two decades, it will be impossible to keep this ever-growing flow of plastics in the economy and out of the environment. To achieve a circular economy we need to reduce the amount of material that needs to be circulated.

Until recently, reuse models were broadly considered to be burdensome or a thing of the past. In the last year, there has been a significant increase in business and government interest, commitments and action on reuse in the form of pilots, research initiatives, and reuse-focused startups. Globally, replacing just 20% of single-use plastic packaging with reusable alternatives is conservatively estimated to be an opportunity worth at least USD 10 billion.

Material circulation refers to keeping the material that packaging is made from in circulation in the economy. This is achieved through the development of a dedicated system which includes collecting and sorting, a physical chemical or biological breakdown process, and then the rebuilding of a material that is reintroduced. Packaging materials re-entering the economy in packaging applications is material circulation, while converting packaging materials into roads is not. Material circulation differs from reuse in that reuse circulates the in tact packaging (i.e. packaging shape is maintained and circulation occurs through washing) whereas material circulation circulates the packaging material (i.e. packaging shape is not maintained and circulation occurs through a breakdown process).

Reuse

Imagine a luxurious, durable ice cream container which keeps the ice cream frozen for hours outside the fridge, and is delivered and picked up in a subscription model. It’s convenient, has a better look and feel, and keeps customers coming back.

Reusable packaging is designed to be used multiple times, for its originally intended purpose, as part of a dedicated system for reuse. The packaging is brought back into the economy through washing, retaining its original form throughout its entire life of multiple uses. There are four different business-to-consumer (B2C) reuse models, differing in terms of packaging ‘ownership’. Refill users retain ownership as in they keep the packaging, while Return users return the packaging and the ownership either moves between business and user or stays with the business.

Reuse models are sometimes considered burdensome or a thing of the past. However, innovative reuse models can unlock significant benefits, enabled by digital technologies and shifting user preferences. Such models can help deliver a superior user experience, customise products to individual needs, gather user insights, build brand loyalty, optimise operations, and save costs. Reusable packaging is a USD 10+ billion innovation opportunity that can deliver significant user and business benefits.

Moving from single-use to reuse not only helps eliminate plastic waste and pollution but also, if done well, offers significant reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other negative externalities*.

Find out more in our Reuse book, which provides a framework to understand reuse, identifies six major benefits, and maps 69 examples from around the world.

* Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Towards a circular economy vol.3: accelerating the scale-up across global supply chains (2014).

Quick Q&A

What is plastic made of?

You could divide it into three categories: fossil-based (oil or gas), renewable (organic, bio-based) and recycled. The vast majority is made from the first category, only a fraction the second, and when we talk about plastic packaging, about 2% is made from recycled plastics.

What is the difference between biodegradable and compostable plastics?

If something is ‘biodegradable’ it means it is able to be broken down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass by the natural action of microorganisms. However, for plastics this term is not very meaningful, as it does not give any information about the length of time taken for the process to complete, or the conditions that are required. A much better defined term is compostable plastic items. This tells us that the items can break down into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass within a specific time frame and under specific, controlled conditions.

Okay, so what if all plastics were compostable?

If an item is compostable, this tells us it can go through a process whereby the item can eventually be safely turned into water, CO2, and compost. Compostable plastics are not a silver bullet solution to plastic pollution, and should only be used for specific, targeted applications, coupled with collection and composting infrastructure.

What are bioplastics?

Bioplastics are either biobased (related to how the material is sourced), compostable (related to how it can be processed after its use), or both.

Can’t we just recycle it all?

Currently, only around 14% of plastic packaging is collected for recycling globally. Without fundamental redesign and innovation, about 30% of plastic packaging will never be reused or recycled. So while recycling is part of the solution, we won’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis.

The majority of plastic packaging items on the market today are designed in a way that means they are not recyclable in practice and at scale.

Wouldn’t it be easier to just ban all plastics and replace them?

It all sounds rather complicated. Wouldn’t it be easier to just ban all plastics and replace them with other materials, like paper, glass, or aluminium?

Eliminating the plastics we don’t need is a key part of the solution. However, we know we can’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis, neither can we reduce our way out. Switching to alternative materials or eliminating plastic packaging entirely, can be considered, though always along with the impacts throughout the entire life of the packaging, and the system that it is a part of.

Exciting innovations

A circular economy is the only solution that can match the scale of the plastic pollution problem.

With a clear course of action and unprecedented global momentum, it is time to ramp up innovation efforts to catalyse systemic change. At a global scale, the number of innovation challenges, accelerators, incubators, and public and private funding is starting to rise.

Here are a few examples:

Edible and biodegradable packaging

Ooho is edible and biodegradable packaging for beverages and condiments made from brown seaweed, a renewable natural resource. It contains the product for the period of use without the need for single-use beverage bottles, cups, and condiment sachets.

The condiment sachets are available on the Just Eat food delivery platform. During the initial trial with ten restaurants, the use of 46,000 sauce sachets made from single-use plastic were avoided. The water capsules were trialled at the 2019 London marathon, eliminating the need for more than 30,000 single-use plastic cups and bottles.

Solid products that require no packaging

Moving from a liquid to a solid product can:

Lower the cost of transport and reduce transport emissions

Be more convenient for a consumer

Increase e-commerce opportunities

Present an opportunity to rethink the delivery model

Make it easier to provide large quantities of product

Allow you to use less packaging material per volume of product

Founded in the UK in 1995, Lush now has over 850 stores worldwide. It sells a wide range of solid products across hair, body, fragrance, toothpaste, and beauty care categories. Most products are sold naked in store, meaning that packaging that was previously required to contain the product (bottle, container, tube) has been eliminated.

Packaging-free food

Apeel is a plant-derived coating for fruit and vegetables which slows water loss and oxidation. It extends shelf-life without the need for plastic packaging, such as shrink wrap on fruit and vegetables.

A single cucumber supplier is expected to eliminate more than 30,000 kg of shrink wrap per year using Apeel. A full life cycle analysis (LCA) has been conducted for Apeel coated products, and they outperform the baseline product in all cases.

Linear or circular?

Company X takes used plastic packaging and turns it into mudguards for their bicycles, street furniture such as benches or roads.

Linear. Yes, the plastic is being used again but it’s being downcycled into a mudguard or mixed with other materials to create a road, and, likely, it will eventually end up as difficult-to-manage and non-recyclable waste sooner or later.

Linear or circular?

Company Y collects used plastic packaging and uses a new technology, called pyrolysis, to turn the plastic back into oil, which is sold as fuel to transportation companies.

Linear. Turning waste into fuel is not much different from burning waste to generate electricity. In both cases, while some one-time extra value is gained from the plastic, in the form of energy, the materials are then lost from the economy, which means new virgin materials are needed to produce the next generation of products.In a circular economy, the circulation of materials aims to keep the materials in the economy at its highest value. The last resort is recycling, but this should result in turning used plastics into new materials. There are difficult-to-recycle plastic packaging items, which pyrolysis can process into a raw material that is turned into new plastics, instead of producing a fuel that gets burned.

Linear or circular?

Company Z has a chain of shops that provide hot coffee to go. The company has decided to give its customers discounts when they bring a reusable cup with them, rather than using a single-use takeaway cup.

Circular. While a takeaway cup is usually used only once before becoming waste, and can’t be easily recycled because it is made from a mix of materials, the reusable cup can be used many times. By offering customers an incentive to carry reusable cups, Company Z is promoting ‘reuse on the go'. Reusable packaging is a critical part of the solution to eliminate plastic pollution and create a circular economy for plastic.

Find out more in our Reuse book, which provides a framework to understand reuse, identifies six major benefits, and maps 69 examples from around the world.

What is the foundation doing for a circular economy for plastic?

Over the past four years, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastic Economy initiative has united more than 1,000 organisations, including businesses and governments, behind a common vision and targets of a circular economy for plastic.

Run in collaboration with a broad group of leading companies, cities, philanthropists, policymakers, academics, students, NGOs, and citizens, it has brought together key stakeholders to rethink and redesign the future of plastics, starting with packaging.

With an explicitly systemic and collaborative approach, the New Plastics Economy initiative aims to overcome the limitations of today’s incremental improvements and fragmented initiatives, many focused solely on downstream solutions. The initiative’s main goals are to create a shared sense of direction and to spark a wave of action and innovation in order to set the world on an irreversible path towards a circular economy where plastics never become waste.

How is the vision acted upon?

To drive collaborative projects and co-shape the plastic initiative, we work with a varied group of organisations including global consumer goods companies, retailers, packaging manufacturers, and plastic producers, along with businesses involved in collection, sorting, and reprocessing. A joint philanthropic-business advisory board oversees the initiative to ensure the inclusion of a wide set of social, environmental, and business considerations.

In October 2018, in collaboration with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment was launched, uniting more than 450 organisations behind a common vision and an ambitious set of targets to address plastic waste and pollution at its source, by 2025. Signatories include companies representing over 20% of all plastic packaging produced globally, as well as governments, NGOs, universities, industry associations, investors, and other organisations. In 2019, the first annual Global Commitment progress report was published, providing an unprecedented level of transparency on how these signatories are reshaping the plastics system.

The vision for a circular economy for plastic is being implemented on the ground by a network of national and regional (cross-border) initiatives, called The Plastics Pact, a globally aligned response to plastic waste and pollution, which enables vital knowledge sharingsharingThe use of a product by multiple users. It is a practice that retains the highest value of a product by extending its use period. and coordinated action. Each initiative is led by a local organisation and unites governments, businesses, and citizens behind a common vision with an ambitious set of local targets. Since its launch, the Plastics Pact has proven to be a unique platform to exchange learnings and best practices across regions, accelerating the transition to a circular economy for plastic.The progress of each Pact is reported publicly every year, in line with common definitions and measurements.

If we want to free our oceans from plastics, we have to do more than just cleaning up. We have to fundamentally rethink the way we make, use, and re-use plastics so that they don’t become waste in the first place. To do this, we need better materials, clever product designs, and new circular business models. Radical innovation is critical to enable businesses and governments to deliver on their targets. Our Reuse book, published in June 2019, provides a framework to understand reuse, identifies six major benefits , and maps 69 examples, providing a basic description of how different reuse models work as well as typical implementation challenges.

-----------------------

Funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation